A body that can get pregnant

Hi all, thank you for being here! As always, I welcome your comments and outreach with thoughts, responses or feedback.

The other day, a male friend of mine said to me offhandedly, I wish my body could get pregnant. He mused, I like being a man, I am generally happy with my body, but I just wish it could get pregnant. It was a casual comment, the ability to get pregnant framed as an interesting curiosity. Unexpectedly, I bristled, felt suddenly angry, tightened the muscles around my mouth to try and maintain a neutral visage. It was odd. Why should I care if my friend casually wanted to get pregnant?

But something about it stuck with me. As I lay in bed later, still thinking about the silly thing, considering my reaction, I realized why the comment plucked a tender string in my chest: a body’s ability to get pregnant, whether or not one actually carries a baby, is so wholly formative, the idea that one could just put a pregnancy add-on to a male body is a ludicrous fantasy. At a moment in the US when women’s right to an abortion is receding, women’s health is systematically deprioritized in research and practice, periods are still taboo, autoimmune diseases in women are reaching epidemic levels, institutional postpartum support for mothers is virtually nonexistent, and childcare eats up whole paychecks, the ability to get pregnant—whether one does or not—shapes one’s whole life.

I wish that my friend knew that his desire for a body that can get pregnant was a wish for a largely different life, a different identity, different struggles and joys. His clear obliviousness to this fact is, to me, a good encapsulation of where our country stands on women right now: oblivious to the needs of a menstruating, childbearing body. This was the source of my reflexing anger at the comment. We treat pregnancy and bodies that can get pregnant in a way consistent with my friend’s fantasy—a woman’s body is just a a normal body (a man’s body) that has a pregnancy add-on. Just a good old standard issue body but with a little nine month splurge!

A regular man’s body that can get pregnant, you say? Sir, let me elucidate for you what else you will get!

***

I was in my late twenties before I learned that there are four phases of the menstrual cycle, which occurs every day of the month, not just five days of bleeding (ah yes, the menstrual cycle, that old thing, the process that goes on in almost every female body for 40-or-so years, and which enables the creation of new humans). The fact that it took so long for me to acquire this basic information, even though I had attended an all girls school for eight years and lived as a female person for over twenty-five, blows my mind. I happened on the information because a friend of mine wrote a blog post on the topic outlining the rise and fall of female sex hormones throughout the menstruation, follicular, ovulatory and luteal phases of the cycle, and the basic impacts these hormones have on physiology and mood throughout the month. Put simply, in the early weeks of the cycle, high estrogens tend to make women feel energetic and positive, and increasing progesterone in the second half brings on lower energy and moods. (In some cultures and eras, this second half of the cycle has been framed as a time of inward focus, calm, and reflection. Amazing what a difference these descriptors can make in how we view an experience.)

Let me give you a small list of the goings on in the female body each month as a result of fluctuating sex hormones. Estradiol in the first half of the month suppresses stress hormones adrenaline and cortisol, while progesterone encourages the body’s production of cortisol, affecting stress levels and irritability; progesterone may contribute to an increase in resting heart rate and a decrease in aerobic capacity and ability to tolerate heat; estrogen is thought to promote carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism, while progesterone seems to inhibit it; why the hell didn’t I ever learn any of this?; estrogen makes insulin more effective, which leads to high production of testosterone in the body; when both hormones peak around ovulation, this is thought to suppress the body’s ability to make sugar from protein and fat (gluconeogenesis), which makes it harder for the body to access quick energy; progesterone also breaks down muscle and is likely involved in renal function and, according to one paper, “the innervation of the diaphragm via the phrenic nerve.” While I have no idea what that means, the point is that sex hormones are involved in a verifiable shit ton of the body’s processes, and the deeper you look, the more you realize the web of impacts that the hormones involved in the menstrual cycle have on the female body. The authors of one paper put it dryly, hilariously, “Fluctuations in estrogen and progesterone during the menstrual cycle can cause changes in body systems other than the reproductive system.” Um, obviously. But then again, when do we ever hear this acknowledged in daily life? In the workplace, where menstruating women spend so much time? Rarely, outside of denigrating comments about PMS. (Even now, writing this, realizing that I have unwittingly written two essays in a row about menstruation, my mind reflexively warns me against it: they are going to think you’re obsessed with menstruation!)

Being able to get pregnant is a foundational, life-shaping quality in a person, affecting so many aspects of life experience beyond the ability to carry a baby. Here’s another obvious one: the burden of preventing pregnancy also largely falls on pregnancy-enabled bodies. I was part of the first generation of girls who started hormonal birth control as teenagers en masse and took it for ten or fifteen years straight before wanting a child. While the official medical line is still that this is safe to do, the small print seems to be getting longer over time. First, there are all “minor” side effects we wave away—mood changes, weight fluctuations, spotting, cramping and so on. I started the pill at age seventeen, and the synthetic hormones caused me to feel weighed down with sadness every minute of the day, as if gravity had increased. Within weeks I gained ten pounds, or nine percent of my bodyweight at the time. Those didn’t feel like minor things to me. The relationship between the pill and various cancers is difficult to analyze—current research suggests that it increases the risks of breast cancer and cervical cancer and may decrease the risk of endometrial and ovarian cancer, but data on this is often conflicting and has evolved over time as the hormones in the pill evolve, so for now let’s just return to the most basic assumption, that sex hormones impact systems throughout the body: it seems to me that taking synthetic hormones for this long must, just must impact the body. Probably negatively. I’m not a doctor, but.

Unable to feel at all good while taking the pill, I chose to switch to a hormone-free IUD in my early twenties. That IUD, I learned later, functions by causing constant low-grade inflammation in the cervix such that a successful pregnancy is unlikely. Constant inflammation? Very cool, very cool, thanks, put it in, no problem. But I was young, bodily damage had not accrued yet, I trusted my doctor. The result for me was seven years of extra-heavy periods and major period cramps. (A viral Tik Tok video showed a group of friends, men and women, trying a machine that simulated period cramps. At one point a woman is standing wearing the machine and saying, “this isn’t as bad as my actual cramps,” and the man is bent over in pain, holding his knees, telling someone holding the controls not to turn the dial on the machine any higher. At the end of the video, one of the men off-screen says, “do you feel them bitches in your back?!” And the woman says, “oh yeah.”) Eventually, my intuition took over—no matter what the current research says, (and there is a long history of under-researching health topics that affect mostly women, which we will get to), it just can’t be good to cause low grade inflammation in one’s cervix for seven years straight, right? That can’t have zero impact on one’s organs or health or fertility, right? I know intuition is not supposed to supersede research these days, but geez, just think about it. So I had the IUD taken out. At some point my mom, a pediatrician, counseled me: “all the birth control options are damaging, so best to just switch it up every so often.” This was also an intuition, a doctor’s intuition, and I have to say, it seems right.

So, you want a man’s body that can just get a little pregnant, you say? Prepare to receive worse healthcare in every way. Until the 1990’s, medical research was done almost exclusively on male mice and cisgender male humans. The given reason was that female mammals are “intrinsically more variable and too troublesome for routine inclusion in research protocols.” In other words, menstrual cycles made research harder, and so women were ignored. Again, it feels almost insane to have to write this, but this (obviously) matters because females and males have real biological and physiological differences, including, in females, lower weight, slower digestion, higher body fat percentage, less enzyme activity in the intestines and slower kidney function. The drug Ambien was metabolized so differently that women taking the approved dose at night were getting in Ambien-induced car crashes the next morning, and the FDA eventually cut the approved dose by 50% for women. A 2009 survey of clinical research across nine research areas such as immunology, general biology and endocrinology, found that only 28 percent of recent studies included both male and female research subjects. In 2019, a repeat study showed that this number had increased to a (still sad) 48 percent of studies including both sexes, but less than half of those analyzed their data by sex. In other words, medical research today still largely fails to consider the needs of the female body, meaning women everywhere are receiving care and taking drugs formulated for the male body at male doses most of the time. Oh yeah, and there’s the documented, systemic dismissal of women’s concerns in doctors offices, a modern manifestation of the historical belief that the womb causes hysteria. Oh god, I can’t even go there right now.

Have I made the case yet that the ability to get pregnant is not just something you might sign up for as an afterthought, as my friend wanted to? Being able to get pregnant is a huge damn deal. But there is so much more, more than one newsletter’s worth. I want to tell you about me, about my deep biological yearning for a baby that arrived like a storm at age 28 leaving all my previous priorities in wreckage, and my infertility journey, my six intra-uterine inseminations and three rounds of IVF, and my breast feeding escapades: my five cases of mastitis (breast infection) and my benign breast fibroadenoma that had to be imaged and biopsied and will be re-imaged every six months indefinitely, and the vascular spasms in my nipples that felt like electric shocks through my breast. I want to tell you about my autoimmune disease, linked to the uniquely dynamic nature of the female immune system, which must flex to allow a genetically foreign entity (a baby!) to grow within it. I want to tell you about my OCD and anxiety, and fascinating new ways mental health is being linked to the microbiome (which, you guessed it, differs in men and women!) I want to tell you about how I believe that my autoimmune disease was caused, at least in part, by my six years as CEO of a startup in masculine, cutthroat Silicon Valley. I want to discuss intuition, that so-called women’s intuition, how it can be life-giving and clarifying, how it can also be seductive and dangerous. We’ll get there, that’s what this newsletter is all about.

We will also get to something else: the way a fluctuating mood can bring a depth to one’s joy and sadness, how it can force reflection and heighten appreciation. The camaraderie that comes with the daily experience of womanhood, how women just know each other’s experience in an intimate, indescribable sort of way that is not public. The beauty in our cyclicality, an experience of descending into depths and rising again with new wisdom, descending and rising, descending and rising. The unmatched feeling of rightness in holding a baby that some women experience. I will say now, unequivocally, that I do not wish for a male body, despite the many advantages of having one in our culture.

I do wish that our culture respected these bodies, honored them, listened to them. In my ideal world, my friend would not say so casually that he wished he could get pregnant, because he would be so well-versed in the critical, life-giving, and also life-changing processes that go on inside a pregnancy-enabled body. Instead, our culture is willfully ignorant of these processes, and willfully deaf to the warning flags that these bodies are now raising en masse (shall we call them tangerine flags? Chartreuse flags? Aquamarine flags?). A sea of aquamarine flags that we must now look at.

I’m looking forward to diving in with you.

— Rae

Author’s note: I am using the word “woman” throughout this newsletter to refer to menstruating people who identify as women. As a menstruating woman, I think and talk a lot about periods and the wide ranging affects that menstruation and pregnancy has on female health, as well as the experience of being perceived as a woman in current American culture. While my own experience and content focus on menstruating people who identify as women, I aim to include and respect everyone across the gender spectrum, including trans women, nonbinary people who menstruate, nonbinary people who are perceived by society as women, and trans men who menstruate. There is such a gorgeous, wide range of valid experiences that I admire and have not lived, so am less familiar. I am always learning and, in the scheme of things, know very little, so if you find anything in these pages exclusive or offensive, please reach out and let me know.

Another note: the set of typically feminine qualities—collaboration, driving towards consensus, asking questions, and nurturing, to name a few—a theme in these pages, can belong to anyone of any gender. I use the term “typically feminine qualities” to refer to those qualities that research has shown more often show up in women, and/or that our culture associates with women. But—and this makes me feel very optimistic—they can be naturally held, practiced, or admired by anyone.

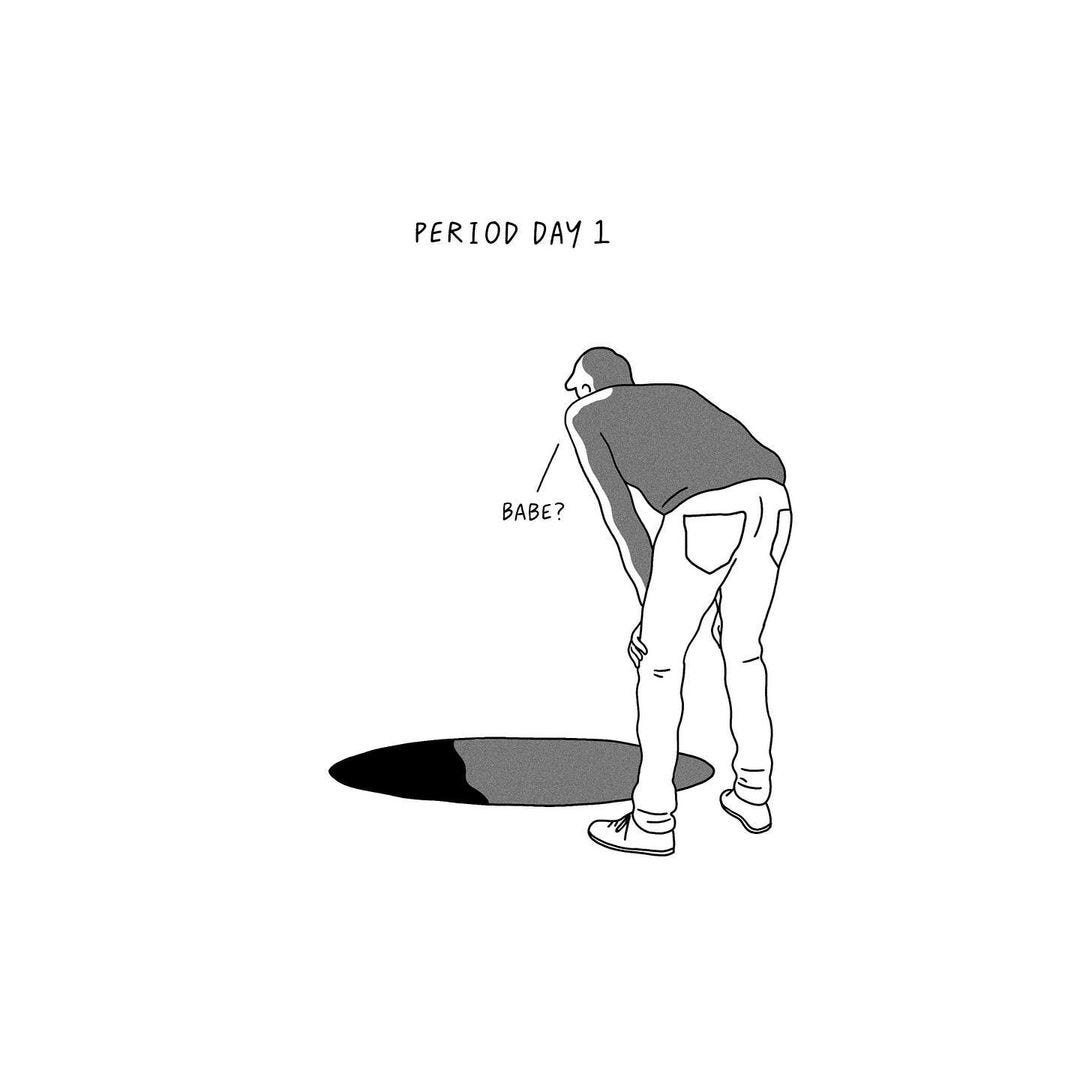

Header image drawn by brilliant illustrator Stephanie Davidson, @asiwillit

Sources

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8508274/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12141881/

https://elifesciences.org/articles/56344

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3008499/

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01836-9

O’Rourke, Meghan. The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic illness. Riverhead Books, 2022