I arrived at the office of a new Functional Medicine doctor for our first appointment. It was 1:30 in the afternoon and sunlight filtered through bright white shades. The room was spare, with a single exam table in the middle and a desk covered in printed papers—my medical history. Two large paintings hung on the wall, an owl and an elephant, the wisdom animals. After making me a cup of elderberry tea, the doctor said,

“This will take three to three and a half hours, do you have the time?”

“I have to pick up my son at five,” I told her. I never imagined that would be an issue. She looked at her watch with urgency.

“Ok then, let’s dive in.”

*

I have been wanting do an installation here about my journey into Functional Medicine over the past year, to share a bit about my effort to understand and address my thyroid autoimmunity and array of other mysterious symptoms, historical and (to a lesser extent) present. My goal is not to provide a blueprint or to recommend anything, but to share some of what I have learned in case it can help you think through similar issues. My journey has yielded undeniable results, it has had failures, it has involved an extraordinarily complicated and expensive array of tests and supplements, it has demanded major lifestyle changes and huge amounts of personal time, it has offered tidbits of clarity and it has generated endless new and unresolved questions. As with almost everything I write about, you will hear some ambivalence. In this case, you will also hear a large dose of amazement and hope.

What is Functional Medicine

Functional Medicine is a branch of alternative medicine concerned with the body’s underlying systems, particularly focusing on the digestive, nervous, and endocrine systems, as well as the patient’s genetics. Gut, brain, hormones and genes. In my experience receiving healthcare, which has spanned everything from medical care at the country’s top hospitals to workshops with breatharians (people who believe humans can live on breath alone), I have found Functional Medicine to be the care discipline that best spans Western and Eastern modes of thought. Of course, it doesn’t do this perfectly, and every practitioner is different, but overall I’ve been impressed by the ability of FM practitioners to move between the two worlds: on the one hand maintaining an open-mindedness to far-out ideas, and on the other a devotion to the available scientific research. It is quite heartening to see pride on the doctor’s face when, two hours into your appointment, she cites the very latest research paper on vagal breathing that is just going to print this week.

The Functional Medicine approach begins with the provider gathering extensive information about the patient’s health and history through questionnaires and testing. This data collection includes whether you were born prematurely, what you eat for breakfast, whether you have recently had your house remodeled, whether your grandfather had any autoimmune diseases, and hundreds of other details. It can include testing for genetic predispositions, microbiome composition, hormone levels, neurological symptoms, and more. The goal is to establish “a detailed understanding of each patient’s genetic, biochemical, and lifestyle factors,” according to the Institute for Functional Medicine, with the goal of producing “personalized treatment plans that lead to improved patient outcomes.”

This all sounds quite dreamy, at least to me, as someone who has gone to approximately three million specialists over the years trying to understand why the hell I’m always tired, and why these itchy rashes, and why these chronic sinus colds, all that effort resulting in a prescription for Flonase. Needless to say, after my first couple of Functional Medicine visits, I was encouraged. Could this be what I had been looking for?

Why FM is relevant, especially for women

The diseases we face today are increasingly systemic, chronic, and multi-factorial, involving complex interactions between multiple body systems. These ailments are notoriously ill-served by traditional western medicine, which silos body systems into specialties.

Autoimmune diseases are the biggest group of these complex, systemic diseases today. Incidence of autoimmunity has tripled in the last thirty years, one in five Americans now have some form of autoimmunity, and scientists are calling it an autoimmunity epidemic. It is estimated that 10-12% of people will develop thyroid autoimmunity, what I have, at some point in their life.

This epidemic is happening primarily in the Western world. One study found that first-generation Pakistani children in the UK were ten times more likely to have type 1 diabetes, an autoimmune disease, than children in Pakistan. Scientists attribute the trend to environmental and lifestyle factors: diet, chemical exposure, and antibiotic use being the three biggies.

In addition to autoimmune disorders, there is a cloud of other difficult-to-understand diseases, all of which mostly affect women. An estimated 75-80% of people with autoimmune diseases are women. Long COVID affects more women than men. Post-treatment lyme and fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome, debilitating diseases which are only beginning to be accepted by conventional medicine as “real,” affect more women than men. Then there are the still-fringe diseases that affect only women, like vaginismus and PMDD. These types of diseases tend to take years to be diagnosed—for autoimmune diseases the average time to diagnosis is 4.5 years, according to the American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association, and longer for the less understood illnesses.

So this is what I mean when I say “mysterious women’s diseases”: those ailments that affect mostly women, that are poorly understood and therefore drag on and on for years without a name or an action to take. It’s worth pointing out that these illnesses are not mysterious because they are intrinsically not able to be understood, but because the scientific community has chosen repeatedly not to focus on understanding them, a history that is detailed exhaustively in Maya Dusenbury’s book, Doing Harm.

A couple key concepts

One concept that has stuck with me as I’ve slowly immersed myself in the Functional Medicine world and made my way through books on mysterious illnesses is that of allostatic load: the burden on a body as it tries to maintain equilibrium. With a lower allostatic load, the body has an easier time staying healthy. A higher load can come from any number of factors—air pollution, pesticides in food, getting yelled at by your boss, poverty, racism, infections, fighting with your spouse.

Sarah Ramey considers this concept in a different way as she struggles with the definition of “stress,” in her book The Lady’s Handbook for Her Mysterious Illness (required reading for anyone interested in this topic). Having been dismissed by many doctors who could find no physiological cause for her debilitating, undiagnosable myriad symptoms, Ramey bristles at the idea that her “stress” caused her horrific reality. The idea is belittling; it smacks of victim blaming; it implies that if only she would have meditated then she would not be confined to her bed, unable to stand for more than a few minutes.

Eventually, Ramey has an ah-hah moment where she realizes that “stress” should be defined far more broadly than working too hard at your job. Stress includes stress on the body caused by eating processed food, and living near undiscovered mold in a rented apartment, and microaggressions at work. Stress also includes internal body systems: the stress of imbalanced hormone levels, perhaps, or the stress of an allergy, meaning that the more the body becomes imbalanced, the more stress it’s under. This broader definition of “stress” acknowledges the potential role of our individual decisions but also includes many, many factors outside of our control. Stress, in this framing, is more like allostatic load. A project to “reduce stress,” then, becomes as much about our world as it is about ourselves.

Some issues with FM

One obvious problem here is that we mostly can’t control our world, and attempts to do so generally tend to be either expensive or isolating or both. Avoiding pollution entirely, for example, is not an option if you want to live near anyone else (or even if you don’t, given the connectedness of all our water and air). I can’t, at least on any timeline relevant to my immediate health, change the food system of the Western world.

This creates a difficult situation for a patient engaging with Functional Medicine to improve her health, and it relates with my musings a couple weeks ago on self-blame. It is easy, if we start to think we can control our body systems, to feel very let down and self-blame-y when we inevitably can’t fully do so. Additionally, the idea that we have all this control, and that health can be achieved through personal body management and purification, creates a highly individualistic and inaccurate view of human health. Moreover, this line of thinking can encourage a general fear of the world, which can easily become excessive.

Another issue is that Functional Medicine approaches are on the far edge of science, whether you are suffering from debilitating ME/CFS or a patch of itchy eczema. There is likely some research there, it may have directional implications, but it is far from conclusive. In any case, the whole premise of the field is that all body systems interact in unique ways in each individual, influenced by unique genes and epigenetics and environment and…well there’s only so much that research can say about your specific complicated situation. Which makes the whole thing very much a practice of trial and error. There are always more foods to cut out, more sleep to get, more supplements to try, more breathwork to do. It is long, it is frustrating, it can become all-consuming.

Then there is the major practical problem with Functional Medicine: it is not covered by insurance and it is expensive as hell. It seems intuitively true that this kind of preventative medicine saves money down the line and is worth investing in, but very few people have that kind of money to invest. You might think that an approach that saves money down the line would be appealing to insurance companies, but because of the nature of the U.S. insurance system, companies don’t expect their members to stay with them long-term. They are therefore not particularly inclined to invest in something like this, even if it is proven to save money in a decade or two. And even if they were inclined, proving that these complex, individualized interventions save money twenty years from now is a long and difficult research slog.

And yet. This mode of care offers me a ray of hope, a vision for the future of healthcare in our country. Not that all doctors should become Functional doctors, not that it’s the holy grail. But the principles appear to offer a solid framework for addressing our growing epidemic of complex autoimmune diseases. And moreover, I have seen results. Let me take you there now.

My Poop Update

A few weeks ago, I wrote about my poop and promised a poop update, so here it is. Below is the summary of findings with my score in five categories of gut health. These are backed up by a 12-page packet of detailed results. I’m not going to go into the details of these scores, but the high level gives you a sense of the trends:

June 2022

January 2023

While I saw some reduction in infection, metabolic imbalance and gut dysbiosis, these results were frankly a little frustrating. Gut dysbiosis is an imbalance in the gut bacteria—too much of one type, too little of another. I had hoped my dysbiosis would be more positively affected by all the dietary changes I’ve made and the fistfulls of supplements I’ve choked down. The reason I care is I’m quite convinced that gut dysbiosis impacts health in numerous ways. Imbalanced microbial communities provide the opportunity for pathogenic bacteria to grow, which predisposes us to certain diseases. Dysbiosis is associated with the breakdown of the gut mucosal barrier that helps modulate which nutrients get absorbed into the body and keeps damaging particles in the gut. Seventy percent of the immune system resides in the gut, and ninety percent of serotonin is produced in the gut. These stats came as a big surprise to me; this was not how I pictured my body coming out of bio 101.

I have read that in the Western world, over a third of people have a chronic gut disorder, the most common of which are irritable bowel syndrome and chronic upset stomach (functional dyspepsia). This figure is hard to believe, but even if it’s half that, it’s still stunning. Moreover, it has been shown that people with chronic gut symptoms have a significantly higher risk of autoimmune diseases. So, it is important to me to address my gut dysbiosis, and I did not see as much progress as I had hoped there.

But, wait!

That’s not all! There is a result that I am really excited about.

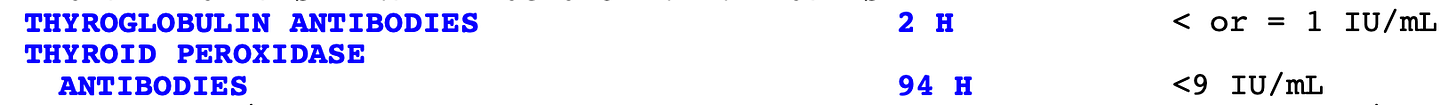

In order to help evaluate the effectiveness of my interventions on my thyroid autoimmunity, my doctor and I measured the level of antibodies to my own thyroid. Antibodies mark foreign invaders to be destroyed by the immune system’s killer cells, so the existence of antibodies to my own thyroid show that my body is marking the organ for destruction. The severity of my thyroid autoimmunity can be evaluated to a large extent by the number of these antibodies floating around in my blood.

This is an area that western medicine confidently says cannot be influenced. There is no medicine to reduce thyroid antibodies. If you ask ten endocrinologists, the specialists concerned with the thyroid, my bet is that all ten will tell you there is no way to impact these antibody levels. Conversely, Functional Medicine doctors believe that there is a way to reduce these damaging antibodies, largely through identifying the diet and environmental factors that are exacerbating the autoimmunity and eliminating them.

After going hard on all my changes for eight months, I was eager and nervous to see what my antibodies would look like. Here they are:

June 2022

January 2023

My most important marker, thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPO), decreased from 556 to 94 between last June and this January. That’s huge…I think!? I nervously awaited the call with my doctor, who confirmed that this magnitude of decline is very significant and can’t be explained by random variation. It is likely a result of the actions I’ve taken. Another doctor told me that she had never seen such a significant impact on TPO with an eight-month intervention.

It goes without saying that I am thrilled and encouraged by this, since my thyroid autoimmunity predisposes me to tons of other health issues. The fact that I can take action to drive it into remission is fabulous news.

I love that FM allows me to see objective results in the labs. A the same time, there are some major subjective outcomes that have been just as welcome. Since beginning my lifestyle changes, the backbone of which is a gluten- and dairy-free diet, I have stopped having menstrual cramps. I no longer experience afternoon energy crashes, which used to hit me most days around 2 or 3 pm. I have noticeably more energy in the evenings—I used to be so exhausted by eight o’clock most nights that I could not drag my heavy bones off the couch to wash the dishes, and I had to leave them for the morning or for my husband. Now I can easily wash the dishes past eight and can even engage in and enjoy nighttime cognitive tasks, like writing. This may sound minor or a little made up if you’ve never struggled with fatigue, but just take my word for it: the change is real and BIG. Finally, an odd but undeniable change: a small but longstanding muscle pain in the lower right side of my back has all but disappeared. Color me shocked.

My approach has not been a panacea, and I am not saying: DO THIS IT WILL SOLVE ALL YOUR PROBLEMS! (One of my main goals, always, is to not say stuff like that.) But it has had a real positive impact, and I do believe it in more than ever, and I am excited to see where I can take it from here.

Conclusion

I think Meghan O’Rourke put it well in her chronic illness memoir, The Invisible Kingdom, (oft-quoted in this newsletter):

“What I had wasn’t just an illness now; it was an identity, a membership in a particularly demanding sect.”

In some ways, this is the price of going down the road of Functional Medicine. It’s a Pandora’s box: once you get all the tests, once you hear the advice, you can’t unsee all the possible actions you could take in service of your health. If you’re like me in this situation, you are all but locked in to a life that will always be at least somewhat focused on actively managing the disease. Some might prefer blissful ignorance, and I would understand that.

That said, I think those of us exploring this route should talk about it more, write about it more, share our amateur experiences more, even though they don’t amount to science.

“Grassroots opinion from people with the chronic disease who want a cure,” writes Functional Medicine practitioner Dr. John Bartemus, “is important in influencing professional consensus.”

Here’s to a healthcare system that puts more emphasis on the type of deep, systemic approach championed by Functional Medicine.

Reading this week: Check out Kim Drucker-Stockwell’s post on Empty Next Disorder. I found it fascinating to read about the empty nest phase as a mom at the toddler phase. It helps me zoom out and hold the whole journey in mind, helps to think about how each phase is special in its own sweet way.

Tell me:

🥼 Have you seen a Functional Medicine doctor? What was your impression?

🚧 Are you relieved by this broader definition of “stress” like I am? What do you think of it?

🏆 If you’re on a mysterious illness healing journey, what has been your biggest win so far?

I remember during the first year of my startup, when my distaste for the whole game was beginning to emerge, sitting in an audience of founders listening to an adored investor, an older man with a deep crease between his eyes and a booming voice, speak about his favorite startup CEO. This CEO was ruthless about hard work, we were told. If this CEO saw an employee reading a newspaper in the office, he would rip it out of the employee’s hands and throw it out the window. I am certain that this CEO got very rich and made the investor very rich, otherwise we wouldn’t have been hearing about him. That it was a gray-haired man on stage and a newspaper featured in the story could have offered me some comfort that this advice might have been dated, or at least not absolute. But I did not feel any relief. Hearing the story, I felt a mixture of disdain for this dreadful CEO character and an overwhelming guilt that I couldn’t operate that way. The whole situation implied, given who was on stage and who was in the audience, that being hardcore and ruthless was the way someone becomes a winner in this place.

My character was the opposite of the archetypal Silicon Valley entrepreneur. I was risk averse, detail-oriented, introverted, allergic to exaggeration, introspective, highly sensitive to the emotions in the room, quick to take offense, and habitually scanning for danger. It quickly became clear to me that these traits were liabilities, beta characteristics that would get in the way of bold vision and ruthless pursuit, and they threatened to render me a failure while all the other valiant and strapping people in the audience around me rocketed forward in the race of life. Perversely, my unfitness for it all made me even more determined not to turn away from the icky scene, but rather to lean in, (and how that insidious phrase goaded me on). The goal posts had been set and I was in the game. I would show that I was a worthy competitor. I would show that I was the type of person that is talked about on stage.

[Edited] This excerpt is from Confessions of an Entrepreneur, which is available now. To read the full essay and get more like it, please consider a paid subscription 🤎

Wow, such a good piece. I appreciate how you present everything in a digestible way (pun originally not intended, but kept on purpose).

My grandmother was a “hippie doctor” in the 1970s before it was cool to be one. I have clear memories of playing at her house while she sat in her chair, reading medical research journals. She had wheels of vitamins she took every day; protein shakes; her house was cleaned with organic cleaners; her air purifiers ran constantly. She was insistent that everyone take vitamins and that we know about the health of our poop. (Very fun when you’re 8.)

An (in)famous family story centers on her bringing out her “Poop Book” at a dinner party to ask a four-star general which of the pictures he most closely related to. 💩 She was serious about gut health, she wanted people to be healthy, and she lived an active life until age 90.

This presented an interesting experience for me growing up as a child. My parents leaned away from modern medicine to a degree that definitely harmed me and my brother (both physiologically and mentally). As a 20-something I had to learn how to go to the doctor, ask questions and evaluate medication, but eventually realized that I needed both sides of the medicine aisle in my life. I want a medical doctor to be able to catch the big stuff. And it’s not lost on me that fertility doctors helped figure out how to help me deliver a healthy baby girl after two consecutive, unexplained second trimester miscarriages. (I also did some acupuncture and active body trauma therapy, so I know those were in the mix, but for me, modern western medicine came in clutch here.)

I’ve likened Functional Medicine vs Western Medicine as two warring kingdoms. They’re (often, not always) insistent on discrediting the other in order to be the top dog. Because being the top dog is what the fight is all about? When, as your piece highlights, the top dog would’ve had you living in misery, insisting nothing can be done about how your body was basically at war with you.

Most of my extended family sees functional medicine doctors (or some who lean more toward witch doctor status if I’m being honest), and I’ve noticed the most common reason they’re hesitant to listen to medical doctors is because they’re so often full of dead ends and prescription pads. Whereas FM doctors tend to have this tireless, keep searching posture -- they keep fighting to help you find a way to feel better. And I can’t blame anyone for wanting someone who doesn’t give up on them.

I also have autoimmune thyroid. I discovered it when I was pregnant at 40, and not soon enough because I had a monster case of preclampsia which, it turns out, are linked. I had been battling weight, fatigue etc for years. I went to an MD that was also into a lot of alternative medicine because I never felt good when my labs said I should. Went through tons of tests. Lots of supplements etc.. but by that time, my thyroid was pretty much burned out. I needed so much supplementation that I didn't really consider any other option. And I chose a doctor who was willing to over medicate me.

I think there are a lot of theories, and anecdotal evidence but in the end, no one really knows. I think it feels good to take action (do something!), and making an effort outside of taking a pill gives you some semblance of control. But at the end of the day, my grandmother grew up and lived in rural Wisconsin. Less pollution. Low stress. Diet quality debatable (with all that white flour). But theoretically less allostatic load than me. But pretty much the same result, a funky thyroid as she wound up with Graves disease in her 40s.