Faking it in the Valley, Part II

Pitching to Y Combinator, my deep dislike for the institution, and my overwhelming desire to be accepted

Thanks for reading! Check out Part I of this story, where I feebly pitch to one of the most famous investors in Silicon Valley and…it doesn’t go well.

Look out for the final installment of this trilogy next week!

Y Combinator is a three-month program to help startup companies fundraise seed money. But, through the alchemy that sometimes turns plain things into highly desirable things, the program is imbued with a certain magical power that inspires awe and respect across the Valley, inspiring a similar level of admiration and deference as an institution like Harvard. It’s hard to overstate the weight that Y Combinator carried in Silicon Valley in 2015. Being a twenty-something with an idea and two employees was the equivalent of Silicon Valley peasantry; being a twenty-something with an idea and two employees in Y Combinator made you something much more notable, much more desirable. Someone, perhaps, who is worth something.

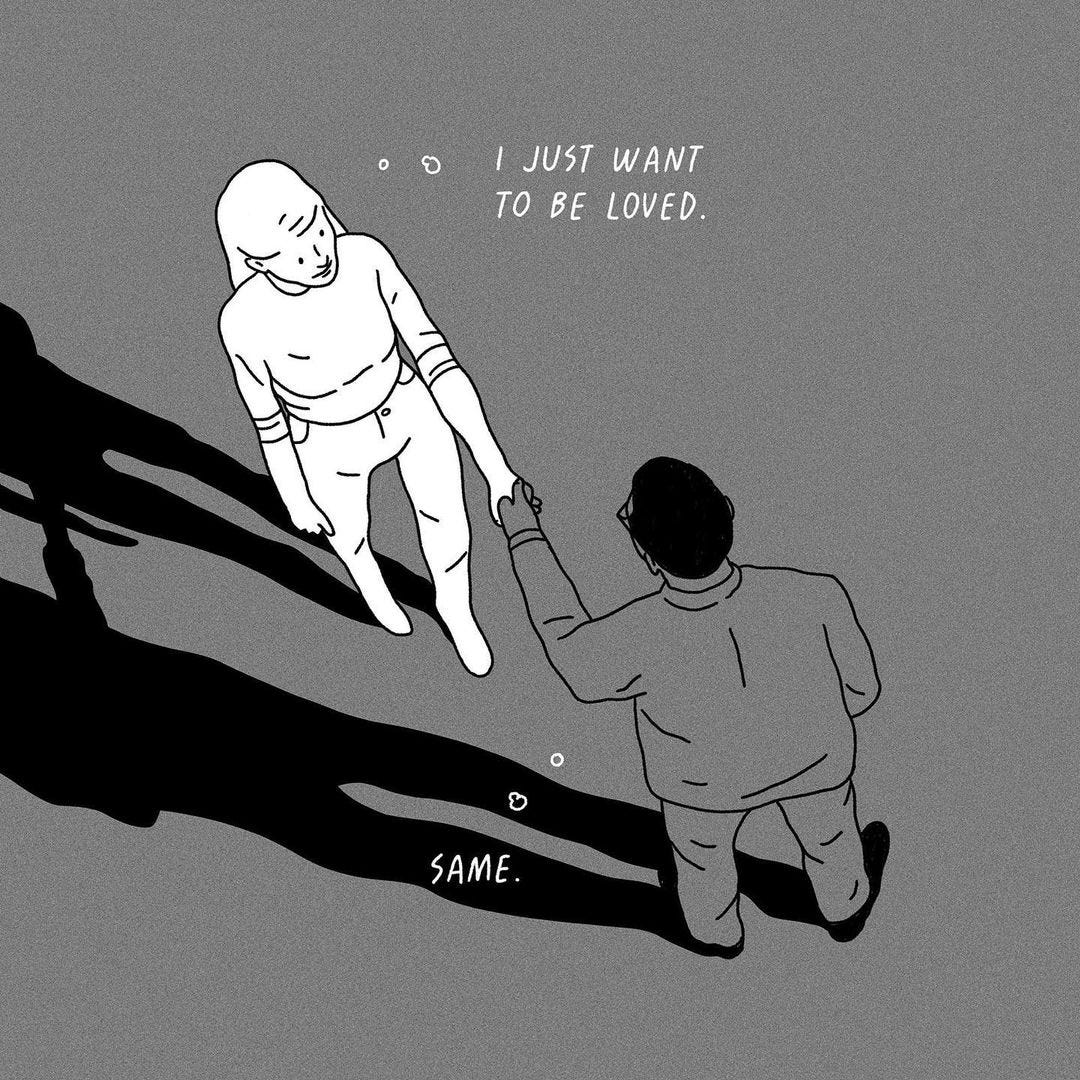

I had a strong distaste for Y Combinator before we ever decided to apply, and I had avoided the possibility for as long as I could. My dislike stemmed from the abominable percentage of female partners and founders, the arrogance that emanated from the men who led the organization in their public appearances, and the seeming dearth of any values other than getting more money. However, as it started to seem like we had fewer and fewer options to prop up our limping “company,” I grimly reconsidered. And once applying to YC was on the table, despite my deep dislike for the institution, I deeply, wholly desired to be accepted into the prestigious incubator. Such is the power of YC.

The application process began with a written form and a two-minute video of the founders explaining the company. Steve and I bolstered our application with a handful of recommendations from current and past YC founders. Once we were selected for an interview, the real work began. Y Combinator interviews are notoriously seven minutes long, and there is plenty of lore surrounding them. We heard that the partners decide within the first thirty seconds. We heard that the number one thing that the partners look for is “founder chemistry.” We were directed to online forums where previous interviewees have exhaustively listed historical YC interview questions. We were neck-deep in YC mania.

…it’s exhausting to be different, and it would also be nice to just belong, so I teetered on the edge between hating the place and wishing it would accept me.

Steve and I practiced for our Y Combinator interview as if we were studying for a final exam. We were both good at that. We pulled lists of interview questions from the internet and spent hours drafting long-form answers to each one. We sat in our glass conference room and split the question neatly between us so we wouldn’t talk over one another–founder chemistry. We solicited such opinions from every guy we knew who had been through the program, and we invited them to our office to quiz us on interview questions. We did, in other words, everything right.

The very first question in the interview, according to the guys, would be:

“So what do you do?”

This was, everyone emphasized to us, the most important question. It was even possibly the only question that would determine our admittance. We dutifully worked and re-worked our answer, carved it up and simplified it and reordered the words. Since I was the CEO, Steve and I decided that I would answer this question, and so I stood in front of him in the conference room to recite our current version. I felt silly and exposed as I began speaking, I didn’t know where to put my hands. I took a deep breath:

We help doctors track and report quality metrics. As the healthcare system increasingly moves towards paying for the quality of care instead of the quantity of care, doctors need to report these metrics in order to get financial bonuses.

It was accurate, but far too long, said the guys. We rewrote it and I tried again. My breathing was unnaturally shallow, my words clipped, my hands folded strangely at my navel:

We help doctors track and report metrics on the quality of patient care so they can collect the financial incentives available for providing high quality healthcare.

We continued to carve it up.

We enable doctors to report on quality metrics so that they can get paid for keeping patients healthy.

The final version was the most visionary and the least specific, and thereby the most uncomfortable to me. It wasn’t really…accurate anymore? That didn’t seem to matter. The goal of a pitch like this was to grab the attention of the least interested, most distracted, least expert person in the room, and get that guy to sit up and listen. It seems more like an advertising effort than an attempt to actually explain the thing, but I guess in some ways we were just creating an elaborate advertisement.

*

The night that we were going to find out whether we got into Y Combinator, we knew that I would get a call on my cell phone if we got in, and that Steve and I would both get emails if we didn’t. That evening I went to an event downtown, a panel on entrepreneurship. I sat in the second-to-last row and surreptitiously checked my phone at five minute intervals. I left as the panel ended, ditching the networking. With my hopefulness waning, I walked out onto Market street in the dark. I walked past a row of windows and glanced at my own reflection: here was someone who did not have the chops to start a company.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Inner Workings to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.