Over the past couple of months, my podcast circuit was flooded with the voice of inequality researcher Richard Reeves, who has been doing the rounds for his recent book: Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do About It. The topic compelled me for a number of reasons: my general interest in gender and power, the fact that I have a young son, and just a natural curiosity about a counter-culture argument. So I listened to a couple of the interviews (and I swear my interest began before Reeves showed up on The Ezra Klein Show, though I know long time readers of Inner Workings won’t believe me 😉).

To summarize, Reeves has done extensive data analysis, mostly on educational outcomes, revealing that boys and men are struggling, with a focus on boys’ performance in school. The top GPA decile nationwide is now two thirds girls, and the bottom decile is two thirds boys. The gap between women and men earning bachelor’s degrees is now 15%, with women bounding ahead of men. During COVID, men dropped out of college at a rate that was seven times more than women.

One of Reeves’ major conclusions is that the structure of school today caters more to the way girls develop and learn. This has always been the case, he says, but has only become obvious now that girls have as much access to school as boys. I heard him repeat one particular claim, which stuck with me: while boys’ and girls’ achievement on standardized tests has more or less reached equilibrium, girls are consistently better at what he calls “non-cognitive skills,” like handing in homework on time. He attributes this to the different timing of prefrontal cortex development.

“So it’s not that girls are smarter than boys, or of course, the other way around. It’s that girls have just got their act together a bit more. They’ve got their prefrontal cortex kicking in. They’re turning their chemistry homework in. They’re getting their coursework done.”

Therefore, as universities place more emphasis on GPA over SAT scores, they are increasingly favoring girls, who tend to get better grades due to, in his view, the overall higher competency at homework handing-in and similar tasks.

Reeves’ view is that, now that we have this information, the project should be to figure out how to educate boys in a way that better fits their learning style. This could include starting boys a year later in school, since boys’ development tends to lag behind girls at key stages, right around the age when kids are starting school and the age when they are starting high school. Society at large, he argues, will be better off with well-adjusted, well-educated boys who aren’t going through a schooling system that is at regularly odds with their developmental stage.

Phew. Ok.

You may be feeling a lot of things right now, depending on who you are. I think all those reactions are totally fine. I am going to take you through a little bit of my thinking on this, and I’m curious how it lands with you.

I feel compelled by the data Reeves presents that there is indeed a mismatch between the needs of our boys and how we are educating them. I tend to agree with Reeves that the goal of our education system should be to serve all children well, and that includes girls, boys, children with learning disabilities, children with different cultural backgrounds, and so on. I am not offended by the idea that we would work to make school better for boys, if we find that it is not working well.

There is definitely a valid argument, voiced by Klein on his show, that throughout all of history various groups have struggled in the American education system, and we have always, as a culture, found that the problem was with the people in that group. Now, boys are struggling, and suddenly the problem is with the system. Put that way, it’s infuriating. I totally understand this argument, and particularly the fear that helping boys in school could very well come at the cost of helping other groups. At the same time, if we assume it’s not a zero-sum game, I personally take the view that helping a struggling group is good for everyone, even if that group has had a historical advantage.

The school/work divide

That said, there is one super glaring topic that Reeve’s touches on briefly, but which I think deserves more focus: the fact that, while boys are increasingly struggling in school and getting into college at lower rates, college-educated boys are definitively cleaning up in the highest levels of our workforce, the places where the major power resides. Women hold 23% of executive positions and 29% of senior management positions. 8.8% of Fortune 500 CEOs are women, and women make up 27% of Congress. One study found that women represent 5% of top-earners who qualify as ‘the one percent.’ Reeves does discuss the fact that men at the very top are still doing really well financially, and he says that the few women that make it to the top are doing pretty well financially. In terms of the lack of women in apex jobs, he chalks it up to the parenting penalty: women are less likely to work their asses off in their 30’s, and that’s what our system requires.

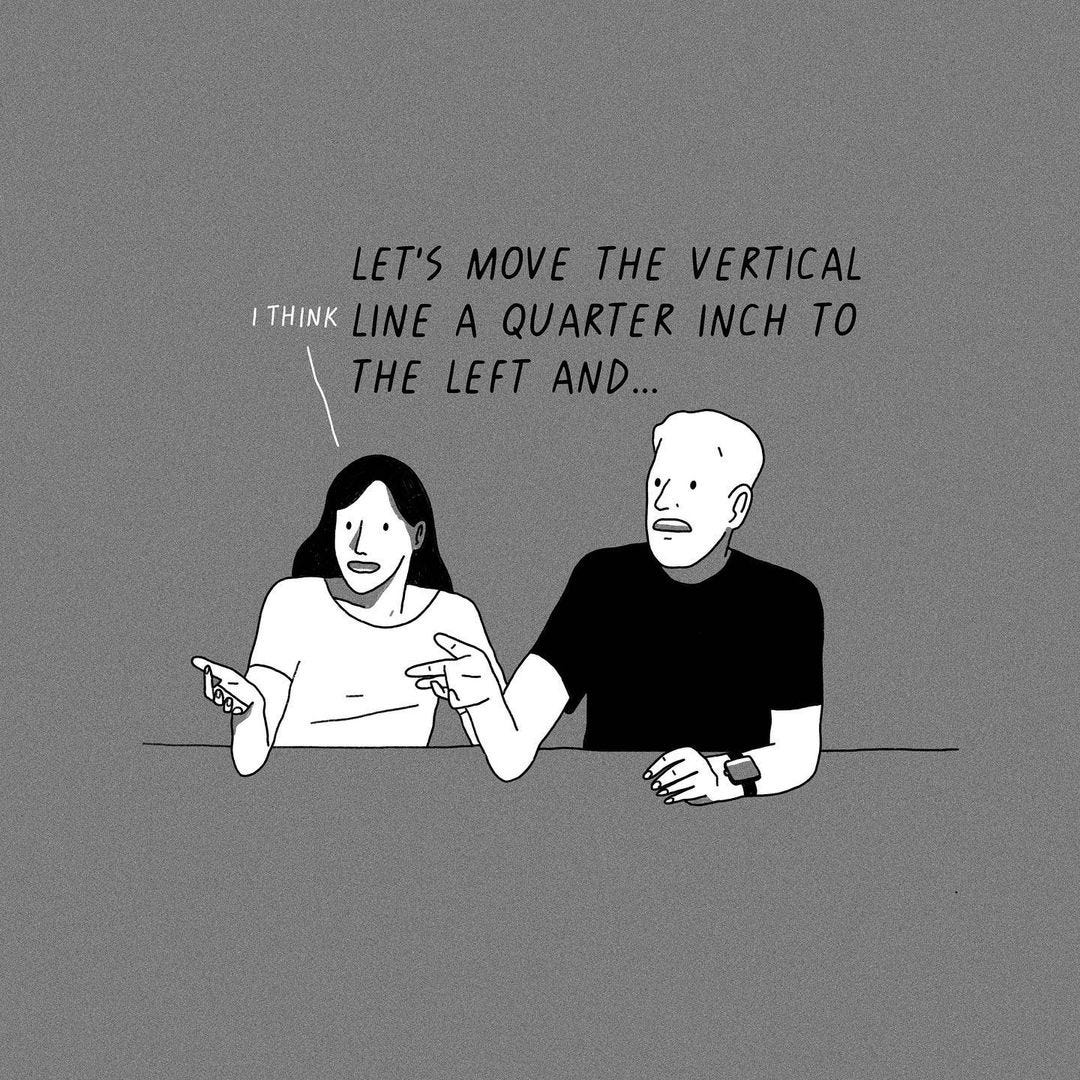

Obviously motherhood is an important factor, but I think there’s more to it than that. This gets at a topic that I have thought about a lot during and after my ten-year career in the halls of power at McKinsey and in Silicon Valley. The executive women that I met, when they were there at all, were always, and I mean ALWAYS, excellent at managing tasks. They were always organized, and they were always competent at running their own projects. They were never the type of executives that spew wild, unrelated ideas and leave their reports to try and make them into something that can be executed. I have literally never met a senior woman executive in the mold of the disorganized inventor or the crazy, untethered idea-woman. I’m sure one or two exist, and I’d love to hear about them if you know one. On the other hand, I have met many such men, who are idolized for their wild ideas, and who rely on an army of junior people to get literally anything at all done. To use Reeves’ words, female executives “have just got their act together a bit more.”

But is that even helpful?

I was excellent at school. All the women I know who have accrued power within the US corporate and political system over the last decade and a half since I graduated were, too. Part of being excellent at school, I am thinking now, as I process Reeves’ words, obviously involved an excellence at handing in homework on time, and other examples of good task management. However, as I ventured out into the professional world, even early on, I started having some inklings that this particular competence not actually helping me in the way I might expect. The fact that I could be relied on to do things on time, always, did enable me to perform well on teams, but did not help me seem “executive.” In every single performance review during my three years at McKinsey, I was told that I needed to work on my “executive presence.” The specifics of how to do this were never detailed, but it seems to me now that it would have required actions like talking louder and talking more often, not completing work even more meticulously and efficiently. The problem for me was that I had practiced and perfected the task-completion competency for sixteen years in school, and I had rarely practiced anything in the realm of “executive presence.”

So, what my experience taught me was that being good at school could gain me entry into the halls of power, but it did not necessarily prepare me to rise. As it turns out, a propensity for handing in homework on time was really not what was rewarded. Unfortunately for women, it seems that we need to both be excellent at the “non-cognitive skills” and possess a big dose of “executive presence” in order to be considered for the top jobs, while executive-seeming men with big ideas can rise without an ability to manage tasks well at all.

Maze design

There was an article a number of years ago in the satirical magazine The Onion that has stuck with me. The article declared that men are better than women at doing mazes, based on a certain maze where men always performed better than women. To get through this maze, participants had to do a number of strength-oriented physical tasks, like fighting a snake and wrestling a bull at the center. Women, for some reason, almost always performed worse, so they must be innately bad at mazes.

Even though it was supposed to be a ridiculous satire, I had never heard a parable that more accurately and succinctly described how I felt working at McKinsey and as a startup founder. I felt I was competing in a maze designed for someone innately different from me. I am sure this feeling will be familiar to anyone who is not born with the narrow set of characteristics that our systems of power rewards: you have felt this if you are neurodivergent, non-white, disabled or queer, if you are introverted, or highly sensitive, or cry easily. Because I had enough of the rewarded characteristics (namely, whiteness) and was able to fake a hard outer shell, at least for awhile, I could succeed to the extent I did. But it cost me everything to operate in a world that was so at odds with what I felt to be my true self.

What Reeves is saying is that today our schools are mazes designed for strengths more often seen in girls. I buy that, and I think it’s a worthy problem to work on. It sounds like many boys are having a similar maze experience as I did, but earlier, and that’s not good. But it’s also important to pair that observation with another one: in the places where power is gained and spent, that maze is inverted. The skills and qualities that are rewarded in school are evidently not the skills and qualities that earn power in our world.

I think it’s important to talk about how people get to the very top, not because these are the people who are struggling the most or who need the most help, but because these are the people who hold big power. These are the people who funnel massive amounts of resources this way or that, and whose decisions most affect the state of the world and the health and wellbeing of humanity. We can work to alter schools to better serve boys, but also, how do we alter power structures to better serve everyone else?

✍️ Join me in the comments

Have you read Richard Reeves’ new book? What did you think of it?

What is your experience with girls and boys in school vs. women and men in the workplace?

Let’s talk about it in the comments.

Hi. Interesting article. The notion that there are styles of learning and approaches to schooling uniquely suited to girls or to boys is demonstrably incorrect. There is no "one size fits all" educational modality that will suit people based on their "assigned at birth" sex. Also if Reeves claims that schooling has always been designed to better suit "girls" than "boys," and "has always been so," he has clearly done little to no research into the history of education. For millennia, women were denied education altogether. For centuries, their educational opportunities have been meagre at best. Now that boys are falling behind in education, some apologists are trying to blame this on the style of education rather than much more important influences that are messing up our sons. What social influences are most powerful in the lives of boys and young men? What examples are being put before them on what it is to be a successful, mature, responsible adult? Further, education itself is under fire and crumbling. Tuitions and cost of post-secondary have been jacked up to the point where someone could graduate as, for example, a veterinarian and not earn enough to pay off education debt for decades. Humanities and arts education, crucial to development of cultural literacy and development of empathy and critical thinking skills and creativity, have been decimated. NOTE: most of the creative, influential thinkers of the past were grounded in the arts, humanities, classics. Young men / boys may have difficulty with longer term focus, self-regulation if they are steeped in gaming, pornography, "Marvel Universe" fantasies of violent heroes with super powers, casual misogyny, and "influencers" (e.g. Andrew Tate), and the runaway insanity of gun culture. Narrowing the foundation of their success/failure to schooling seems naive and the notion that this culture's approach to education is designed to suit girls is utter nonsense.

Couple of anecdotal points from a (a) tutor and (b) man.

1. I have definitely seen the difference in organisation/sense of responsibility between my male and female students, particularly once they start hitting puberty. There is no less organised person than a 15 year old boy. I have one student who turns up without a pen every single lesson. Every. Single. Lesson. You would think that, after 2.5 years of this, he would learn that he needs a pen. He hasn't. He doesn't even think of it!

2. I like Reeve's solution to this of holding boys back a school year. Seems like it would benefit the boys without holding the girls back. Any outliers among the boys can be sent ahead a year as often happens now.

3. Seeing a lot of anger in the other comments here about how other groups were held back from educational opportunities for a long time and how we shouldn't start changing the system now because its seen as not working for boys. While I can certainly understand where it's coming from, I don't think it's really practical to let those sentiments guide policy. If we want equality of opportunity for all groups then we should try to create that, regardless of past injustices. I completely agree that we haven't lived up to this ideal in the past, or ever, but that doesn't mean it shouldn't be the guiding ideal. Also, if I understand Reeves properly, boys are performing worse than girls in all ethnicities/races, so its damaging other minorities groups too.

4. On difference in outcomes beyond school, I suspect that a lot of the people who make it to the top are even more homogenous than we commonly think. At first glance, one can look at top positions in government/corporations and see mostly men, yes. But even that is a tiny subsection of all men. I think those positions select for very specific personalities. People who probably score really highly on things like disagreeableness and conscientiousness and the ego required to go for those positions. This means you're looking at the top few percent on the distribution and there just tend to be more men on that side of the graph. This is not to say there isn't gatekeeping, or prejudice, or any other obstacles slowing women down, just that the system is not necessarily geared towards men, per se, but to a very particular group of people, within which men tend to be in the majority.

5. The traits I mentioned in the point (4.) are not necessarily 'good' things. Having the willingness to work 60 hour work weeks for decades, the willingness to walk over others to advance oneself, or having the ego required to think that it should be you in charge, might make one a good CEO or adept on the campaign trail, but it doesn't guarantee one a contented, fulfilled life. Seems almost trite to say this but climbing the corporate ladder might bring you more money, a larger house, fancier dinners, but it doesn't bring happiness by itself. In fact, I suspect a lot of those traits actually make that harder because you can't stop trying to climb. I imagine those people are never sated and all always looking for more status, wealth, prestige and so on.

I don't want to put words in your mouth, Rae, but from your previous posts it seems like you realised you were chasing that path yourself, to an extent. Then you realised it wasn't for you, it's basically a bullshit life, so you stopped. My guess would be most people, both men and women, have the same realisation and stop trying to chase the bullshit. Because really, how many people lie on their deathbeds and think, "I wish I had made that extra promotion."