I Bought 30 Acres With 7 Friends: A Starter Guide to Communal Ownership

10 Tips for owning a shared space with friends

Hi Inner Workings Readers! If you’ve been here a little while, you know I don’t typically do “guides,” or listicles or Ten Ways to Blah Blah, because, yeah, the world has enough of these. But today I am going to try that form out, because if there is any how-to information that I think is worth spreading, it’s this: how to start your own communal ownership project.

Do you like this? Do you want more? Leave a comment.

A little background

I co-own 30 acres of woods in the Santa Cruz Mountains along with my husband and seven of our friends. You can read more about the project here, but, in short, we are just entering our fifth year of owning this magical spot, collaborating on our forest canvas, creating projects together, learning about land stewardship, camping, doing forest management, attempting to maintain our ever-broken brush mower, putting on weird plays, and generally hanging out together. It has been incomparably rewarding. It has been the thing in my life that I would unequivocally categorize as a dream come true.

It has also been hard. It has taken a buttload of work. It has required years of devotion before even buying the land, and even more devotion once it was ours. It has required hard discussions among friends about money. It has involved disagreement and tension. Not to mention that it is easier these days to summit Everest than to get nine people on a Zoom call at the same time, ever, let alone in person.

A lot of people in my generation have a dream like ours; it is obvious that we are collectively craving more community, less hustle, more wide open time, more fresh air. More trees, goddammit. But because this is a big endeavor, and because it’s inevitably going to be hard, it’s really intimidating to start even thinking about what your version of communal ownership could look like. So I wanted to provide a brief starter guide based on our experiences so far. As always when I talk about the way I did something, I want to give my standard caveat: just because this was worked for us doesn’t mean it’s the one right way. My goal here is to inspire, not to be prescriptive.

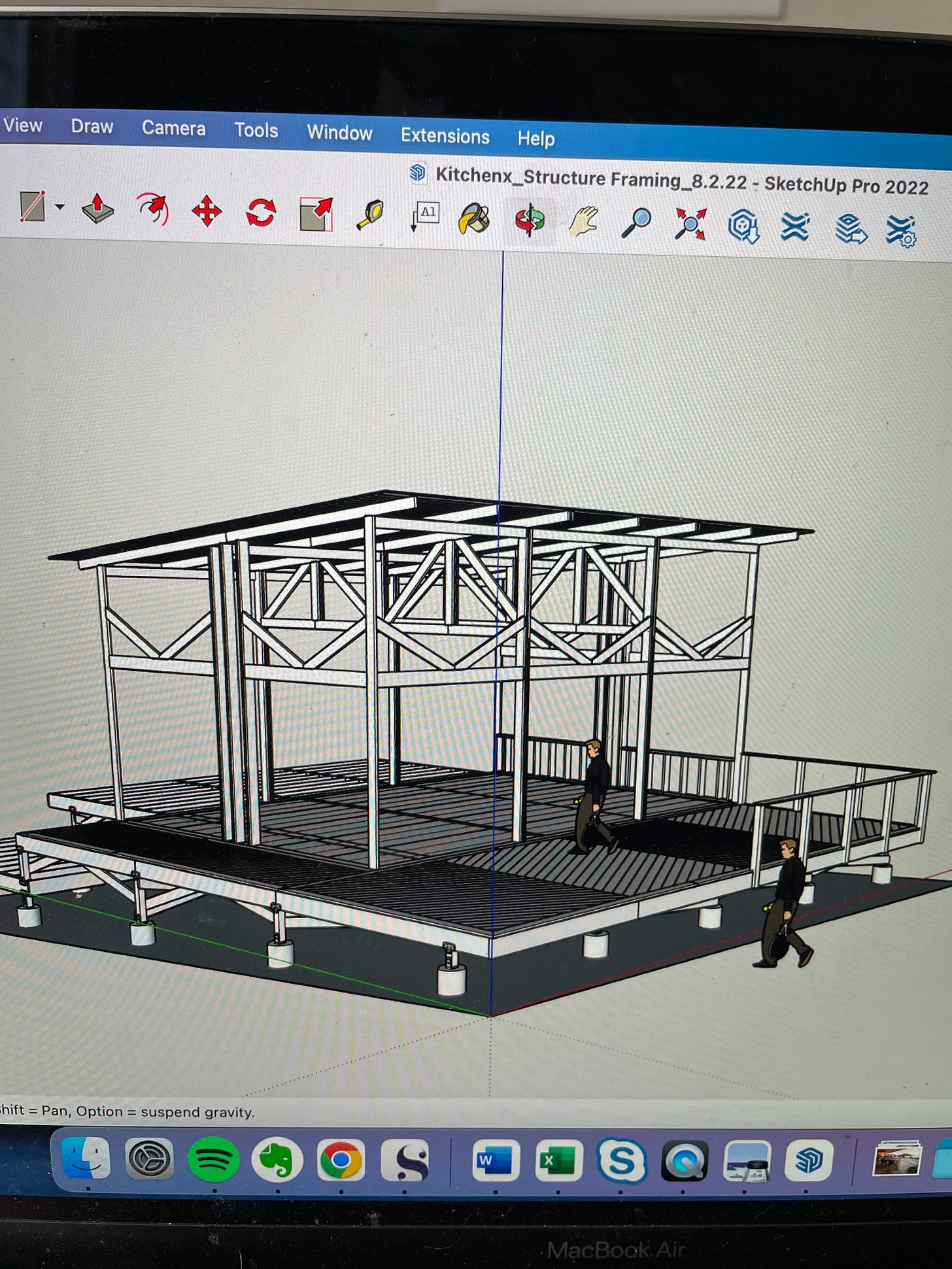

Speaking of inspiration (and because I’m proud of this): I want to show you a photo of the progress on our community lodge. We have been working on this for two years now, completely DIY, led by my dad,

, who used to be a contractor. I cannot exaggerate how beautiful this looks to me, not just because it IS beautiful, but because I screwed in those joists with my baby on my back, and my friends and family framed those walls and raised those rafters.Ok, so, you wanna do a communal ownership project… let’s dive in. Here are ten tips for getting started.

1. Talk about it early and often

It will never happen if it doesn’t get talked about. And talking about it, at first, can feel crazy. Maybe you can’t imagine how this would fit into your life right now. Maybe you have no idea where you’d get money for it. Maybe you’re scared people will say, “oh yeah, everyone has that dream.”

Talk about it anyways, because the more you talk about your idea with people you love and trust, the more it will start to transform from a pipe dream to a tangible idea to a real possibility.

Talking about is also the first step in forming a group to do the project. Some people will say “sounds cool!” and then never bring it up again. Other people’s excitement will lead them to schedule a time to go for coffee and just talk through how it might work. Six months in, you will start to get a sense of who is serious, and that is an important first step.

2. The planning is the project

Talking about a potential project is the first step, and then, once there is real shared interest, the planning starts. Don’t disregard this phase as something to get through to get to the real community stuff, this is the real community stuff. The steps towards realizing a communally owned space involve the real, nitty-gritty, back-and-forth collaboration and compromise of community-building, and I will outline some of these steps below.

The key is, as you go through these steps, take seriously the project of bringing the whole group along in the planning. This is the first place where you have a chance to test out how the group operates together, how people handle conflict, whether people are reliable, whether their excitement for the project can withstand the shitty parts. For people who have not previously worked together in this way, the planning process is the first major opportunity for the groups to form and gel.

3. Establish, a clear, shared philosophy for decision-making

The foundation of successful communal ownership is decision-making: ultimately you are all signing up to make a lot of decisions together over many years. The philosophy of decision-making is of utmost importance. Is there one leader who everyone else defers to? Are decisions tied to votes, and does someone with a bigger financial investment in the project get more votes? Is this a consensus-based process? Are people OK with casual decision-making? What types of major decisions require a formal process? These are all critical questions, and the discussions among the group about how to do this can be totally fascinating.

In our case, we determined a few core principals:

Voting power is not tied to dollars invested, one person gets one vote.

Major decisions require consensus (and we have made an effort to define a “major decision,” like those that require people to put in money or change the landscape in a meaningful way).

We make bigger decisions via monthly group meetings which happen on Wednesday evenings, and smaller decisions asynchronously via Discord.

We definitely slip up. We make a decision at a meeting when someone is missing, and we forget to loop them in. We decide something on Discord and someone doesn’t see it. Someone buys a new gadget for the kitchen and other people don’t like how much counter space it takes up (is the acquisition of an air fryer a major decision?). Shared decision-making is one of the hardest parts of this, and it also happens to be the essence of community-building. Our group tends towards forgiveness when we make a misstep, and people are good at voicing dissent kindly and making changes to the plans when needed. This is all critical: decision-making will never go perfectly.

4. Look for overlapping long-term vision and flexibility

When we were first looking for land, a lot of people told me stories about some other family or group that co-owned a house or a property and it all fell apart. Usually the story had some element of conflicting visions: one brother wanted to rent out the place as a revenue stream, the other brother wanted to have it as a weekend retreat, their relationship fell apart and they had to sell the place.

This definitely highlights the importance of a shared long-term vision. You don’t want to get into the deal and then a few years later realize that everyone wants conflicting things from the place.

That said, I think it’s unrealistic that everyone would have the exact same vision for something like this, and part of the beauty of a group project comes from the varying ideas in different minds. In our group, we have people who want to use the land primarily as a completely serene and meditative place of solitude, and other who want to use it as a community gathering place, an outdoor art center, and a music venue. These visions actually can coexist with creativity and flexibility, but it wouldn’t work if one person ONLY wanted to ALWAYS have COMPLETE solitude and NEVER have groups on the land, for example. Some divergence in vision is ok and even good, but make sure no one is 100% determined to execute only their exact specific vision without room for other ideas.

5. Expect to commit a lot of time up front

Expect to spend a lot of time on this, and expect that your will underestimate the amount of time required. Before a communal purchase, there are planning meetings, visiting properties, hammering out legal agreements, defining a financial structure, and these things take time. Ideally, at least some of these activities sound fun to you, and the rest sound worthwhile in service of the project.

In our case, every owner was meaningfully involved in the purchase process. There were certainly people who took the lead on various parts—I planned a lot of the site visits, another person did the financial modeling, another person created a lot of documentation on decision-making and vision.

This connects to #2: The Planning is the Project. I would be possible to have one leader take all the initiative and spend a ton of time and send updates to a bunch of more passive members who don’t commit a lot of time. In this case, I think the resulting project would look very different from ours. Whoever spends time up front will probably also be spending time down the road, and so spending time up front is important practice and and indicator of what’s to come.

6. Know the key documents

LLC agreement (or other legal structure)

You will need a legal way to own the property. While this isn’t my area of expertise, there are many ways to do this, probably the simplest and most common being to create a limited liability company that is jointly owned by all the members, and which owns the property. Creating this entity and formalizing it in a legal agreement will probably be best done with the help of a lawyer.

Operating agreement

In addition to the basic legal structure, you probably also want to have a written operating agreement that outlines key terms of operation, like how the group makes major decisions, and what comprises a major decision. Can someone exit the project, and if so, how? What happens if someone dies? What happens if we each have twelve kids and then die? All are important scenarios to consider ahead of time, (except the twelve kids part), and an operating agreement is where you can put it all down in writing.

Financial model

You will probably need a financial model to calculate and track each person’s ownership share. You may be able to pull off something very simple, where everyone invests the same amount and owns the same percentage in perpetuity, but there are a lot of other considerations. What if, down the road, someone wants to invest more money in improving the property? How will that contribute to ownership? Will you have a mortgage, and if so, is everyone paying the same amount each month?

In our case, owners put in different up-front amounts and contribute different amounts monthly towards our mortgage. Different owners have further invested different amounts in improvements in the four years since we bought the property. The resulting ownership share of each owner over time is established and tracked in our financial model.

7. Be prepared to talk money

This one is probably obvious by now, but there’s a lot of money stuff when you own something communally. Unless you have a group of people who all have lots of extra money, you will need to go deep on individual preferences and ability to contribute.

The good news is there are lots of options. People could make equal investments or unequal investments, some people could pay more up front and some more on an ongoing basis. Whatever you do, though, you will probably know more about your co-owners’ finances than is usually culturally appropriate, and they will know more about yours, and you have to feel comfortable with that. Indeed, it is this kind of culturally unacceptable, sometimes awkward intimacy that makes group ownership a little magical, and moves relationships into a familial realm.

It also important to talk explicitly about how money affects power and decision-making. There may be a formal process by which bigger investors get more say. But there also are the informal dynamics to consider—If I put in a lot more than you, would there be some subtle pressure to defer to my opinion?

Our approach was to allow unequal investments, this is what made the project possible at all. We also decided that investment level would not affect decision-making power—one person, one vote. Married couples also contribute money as individuals and vote as individuals. These are all decisions that work for our group, but there are infinite permutations to consider.

8. Shape the project around the group’s interests, and be realistic

Does the group have a vision for building things, but no one has time to be there other than weekends? Is anyone in the group handy? Is anyone interested in learning how to use a saw? If not, that’s fine, but it might be worth scaling back the construction ambitions.

There are some things that almost certainly will need to be done in a communal ownership project: financial modeling, legal agreements, a real estate transaction. Is anyone comfortable talking to a lawyer, or is anyone interested in learning how?

Do not underestimate the ability of people to learn when motivated; you can totally go from never using a spreadsheet to making a financial model, they key is just that someone needs to want to. In service of building our community lodge, I learned SketchUp so that I could do the initial visualization and modeling. I had never used CAD before but was really motivated to learn in service of this project, and that was enough!

9. Expect group member engagement to ebb and flow

If you’re like us, people get new jobs, they leave their jobs, they have babies, they travel. Unless people are living in the communal space full-time, individuals probably won’t always be available to give a ton of energy to the place.

The good thing about a group is that at any given time, there usually is someone or multiple people who do have more energy and time and interest in the project. I find this particular element of communal ownership totally wonderful. Since buying the property, our group has collectively had five babies, and obviously the new parents were out of commission for awhile each time. But other people were there, keeping the energy going, keeping the place alive and beautifying and creating.

This type of project is a long haul, and it is best to view progress and contributions over a long period of time. In my view, the ideal situation is that people’s engagement ebbs and flows, and in this way everyone carries the project forward in different ways at different times.

10. Think outside the box

Even though I’m writing a “ten ways to…” article, I encourage you to generally close your ears to conventional wisdom and consider what and how to make this project work for YOU and YOUR GROUP. So no one’s ever heard of doing it this way. So your lawyer looks at you weird. So your brother-in-law says, “that’ll never work.” Be gone, naysayers!

There was one clause in our agreement that made this whole project happen. We had found a property we loved, and people were on the verge of putting in real money that would really be gone from their bank accounts if we went through with the transaction. Though the group agreed that this was not primarily a financial investment, it still felt uncomfortable for many to put money into something with no promise or clarity about when exactly they would see the money again. We had structured the agreement such that it was fairly hard to leave: the group had to agree to buy out the departing owner, or had to unanimously agree on a new owner, otherwise you couldn’t sell your portion until the whole group decided to sell. This meant that there was no guarantee you’d see that money again. This felt uncomfortable. But we didn’t see another way.

Then one of our group invented the twenty-year out clause. What if, in year twenty of owning this property, we said that anyone who wanted to sell could. After twenty years, if someone wanted to sell, the group had to buy their shares or else sell the property. Until year twenty, the preference is given to the people who want to stay. At year twenty, the preference, then, is given to the people who want out. That would be around the time that many of our kids might be heading to college, maybe a time when people would want liquidity. It worked for us. Everything clicked into place. People felt good and confident, exactly the way you want to start out a big project. Who knows if anyone had done this before, and who cares. It was a perfect solution for us.

Bonus tip: be silly

One additional success factor for us has just been to bring silliness in whenever possible. There’s a lot of serious and sometimes boring stuff related to communal ownership, and we need to laugh in order to keep it all fun. For example, we assigned everyone ministries based on their interests and christened our new ministers in a ceremony. We have a Minister of Power, for example, who takes an interest in our solar and electrical, and also manages our LLC agreement. Our Minister of Maps likes to make maps of our land and our dreams. The Minister of Skies keeps the bees and also imagines zip line creations (yet to be implemented).

That’s all from me…now go forth and imagine what your group could do!

✍️ Want to know more?

Do you have a dream of owning some type of property with friends? Any thoughts on being good stewards of the land?

Consider this comment section an AMA (Ask Me Anything) on communal ownership!

Already calling dibs on a Ministry of Silly Walks.

Rae! It was so fun to read about your experience buying and building on communal land. This is my dream, or maybe my nightmare, who knows. I've lived communally in many periods of my life, but never with ownership. This makes it feel like it could really happen! Thank you for sharing.