Wanting to slow down

But also not wanting to

In her book Wintering, Katherine May argues for the necessity of dormant periods in life: times when we do much less, turn inward, and focus on healing. With the voice of a wise aunt, May lays out the case that a life will necessarily contain these periods of inwardness, slowness and, honestly, pain, and that turning towards these times and welcoming them in makes for a fuller life and a wiser self. She writes,

Doing those deeply unfashionable things—slowing down, letting your spare time expand, getting enough sleep, resting—are radical acts these days, but they are essential.

I read this book like a thirsty person finding water. The concepts were not new to me (and in fact, May has made such unfashionable ideas sort of fashionable), but to read a whole book on the value of slowing down, argued with such unwavering conviction, validated an internal voice that had been beseeching me to do just this for years. Within the context of Silicon Valley, where I started, ran and sold a company in the 2010’s, the idea of slowing down was an anathema, the most telltale sign of weakness and insufficiency of will. Resting did feel radical, and so once I was no longer immersed in my startup, I was determined to winter. I had a unique chance to do so, a break between things, and the rare financial ability to choose how I spent my time for a period.

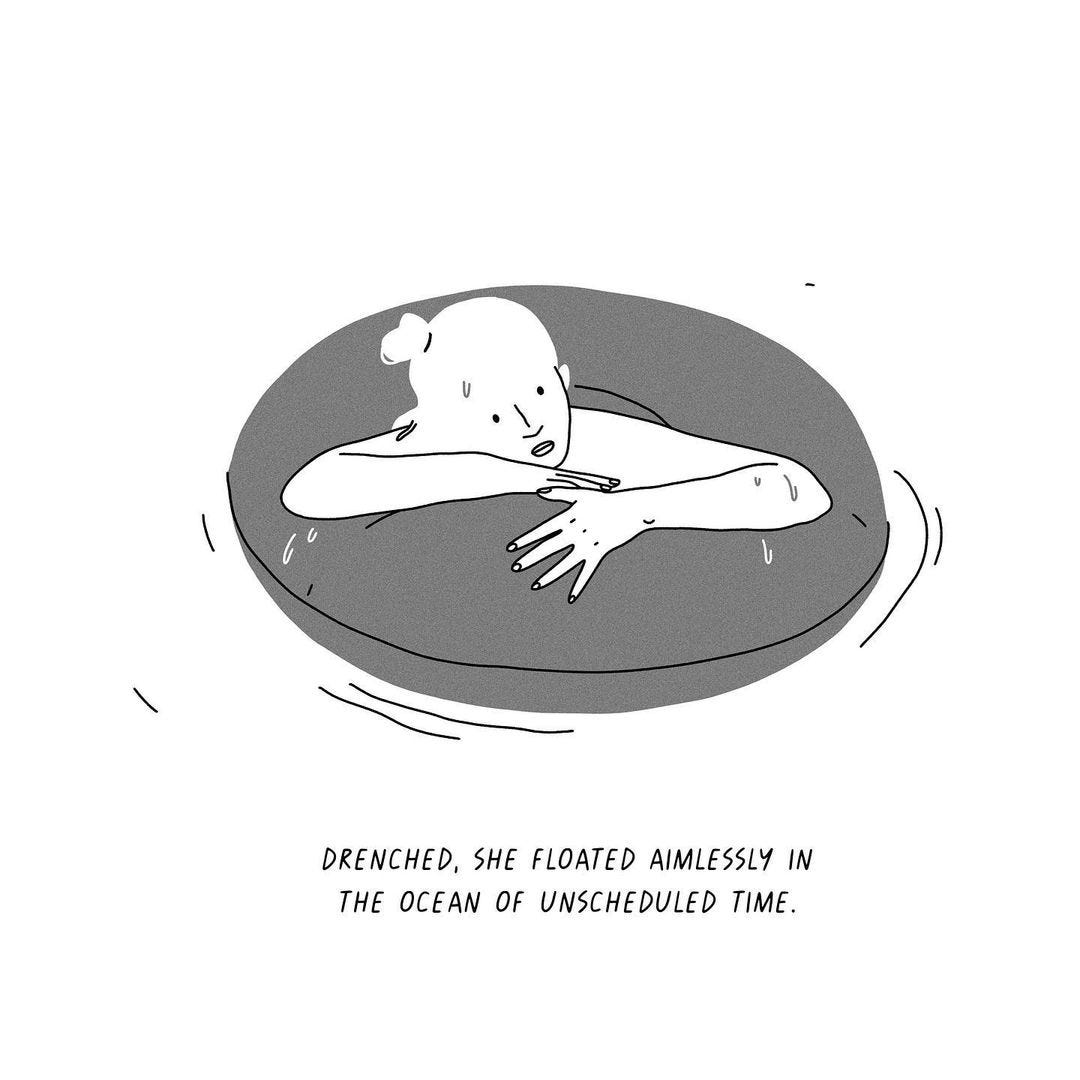

However. I quickly learned that I preferred to winter while also taking writing classes. I also preferred to winter while drafting one new essay every week and submitting work to literary magazines and volunteering at a local community organization. I wintered best while taking, on average, two trips out of town per month and also learning CAD modeling for a cabin I wanted to build on a plot of land that I co-own with nine friends, and I wintered while also going through multiple back-to-back IVF cycles to try and have a baby, and also while doing one-off consulting gigs. Finding myself sick with a mild case of COVID and prevented from doing all these tings for, say, four days, I felt like crawling out of my skin. Even such a short, but real, break prompted me to wonder what am I even doing with my life?!?

And so, it seems, if I want to winter, to actually winter, it will take more than just reading a book and having the time available to do so. And so, the question I have for myself is, do I actually want to slow down? Intellectually, I believe in the idea. I am certain that I have made myself sick from work stress. I am fully convinced that the American pace of life today is one hundred percent insane, even compared to modern life basically anywhere else. Americans work nearly 300 more hours per year than British workers and 440 more hours per year than the Germans. Twenty-three percent of Americans have no paid vacation or holidays, while European countries typically mandate at least twenty paid vacation days per year.

I also completely buy into the idea that there are phases of life: energetic phases, restful phases, phases of output and phases of reflection, phases of joy and phases of mourning. How could it be any other way? But I never practiced phases, what I practiced was being very good at school every year for sixteen straight years. And—here is the key point—in so many ways, being very good at school, and by extension being very good at work output, is who I am. One of my most deeply held beliefs is that my ability to be highly productive has gotten me everything I have. So of course I feel highly attached to this quality, of course I will throw up all kinds of protective barriers around it, of course just believing that wintering is good will not suddenly enable me to slow down and do less.

Ultimately, I think the ideal state would not be to give up on or demonize my productive abilities, not to renounce hard work, but to be able to truly turn it off for a season when my life needs it: when I’m going through health challenges, or a family member is sick, or when the emotional turbulence of infertility is overwhelming, or when there is a tragedy. In these times, I would like to be able to trust that my spark of energy and output will not be lost, will inevitably strike again. This is hard to do. I’m not sure exactly how to get from here to wintering—probably, like any new skill, it will involve small steps. I’d still like to try. At the same time, I don’t know how far I’ll get, since it requires so much unlearning.

What I am interested in now is how to raise my son in a way that enables this shifting between phases of life more easily than I am able to. Katherine May tells a story of a period of time where her son became completely miserable in school, and she made the decision to take him out and homeschool him for awhile. In other words, she decided to walk the walk. This is what we do, she taught him through this act, we listen to ourselves when things are really dark, we don’t just ignore it and push through, we make changes accordingly.

In the same situation, I honestly can’t really imagine doing what she did—think about how much work would be disrupted if I suddenly had a child at home for nine months! But I would like to be the type of person who makes that same decision. And for now, I am going to simply keep that in mind.

—Rae

Header image by Stephanie Davidson, @asiwillit

While in a postdoc in molecular biology we found out my eldest was developmentally delayed. I made the decision to stay home with them, which essentially ended my career. It was not easy. I found a new community among homeschoolers, and it was without doubt necessary for my child, but my ego did not like losing the cachet of being a scientist.

Love this reflection ❤️ Wintering feels like a core tenant of my personality (lol), but I’m definitely learning how to lean toward productivity more and more through things I love, rather than things I feel obligated to do. Thank you for this reminder!