Confessions of an Entrepreneur

How I won and what I lost - greed, misery, and a house on a hill

Confession 1: What

When you pitch your startup in Silicon Valley, your personal story must demonstrate how everything in your life led you to this very moment, showing that you are singularly capable of bringing this exciting and novel idea to fruition. The entrepreneur disrupting the sneaker industry says, “I recall my struggles tying shoes at four years old…” and documents the frustrations he felt throughout his life regarding the lack of shoe machine-washability, how his shoes hindered him in his athletic career, how he came to realize that everything—athleticism, innovation, space travel, the very essence of human wellbeing—comes down to shoes. And he is out to fix that.

I told such a story about my own startup, like everyone else. I started a healthcare technology company in 2015, which would allegedly revolutionize the quality of healthcare in our country, a mission, I said, born of the years I had spent struggling with chronic health issues. My mother spent her career as a doctor and became disillusioned with the insurance-led rat race that the profession had become; my father is a computer scientist: how poetic that their daughter would start a healthcare technology company. You could call it fate? This is how I told it in pitch meetings, at networking events, on panels.

What we actually did, plainly, was provide a software tool for doctors to perform a required reporting task, sending metrics on their patient care to Medicare, the government healthcare program for the elderly. We basically offered a service like TurboTax to help people more easily do some government reporting, and there were plenty of established small businesses doing the same thing with more excel spreadsheets (the disruptees, if you will). My co-founder and I used to joke that the competitive advantage of our company was that it was way too boring for most entrepreneurs to even consider doing.

While I do think we did the government reporting fairly well, at least in the later years, we were pretty far from revolutionizing healthcare. Everyone needs to start somewhere, and that wasn’t what caused me so much angst. What grated against my conscience was the fact that I couldn’t just say what we did. What nagged at my brain stem was that we picked the business primarily because we thought it was a good business, but that wasn’t reason enough in Silicon Valley, and I felt compelled to bring my personal health and family lineage in to back up the story. My story was close enough to the truth that it could be called the truth, but I can’t call it truth because, after all, I didn’t believe it. I suppose, then, I would call it a lie.

Confession 2: Who

I remember during the first year of my startup, when my distaste for the whole game was beginning to emerge, sitting in an audience of founders listening to an adored investor, an older man with a deep crease between his eyes and a booming voice, speak about his favorite startup CEO. This CEO was ruthless about hard work, we were told. If this CEO saw an employee reading a newspaper in the office, he would rip it out of the employee’s hands and throw it out the window. I am certain that this CEO got very rich and made the investor very rich, otherwise we wouldn’t have been hearing about him. That it was a gray-haired man on stage and a newspaper featured in the story could have offered me some comfort that this advice might have been dated, or at least not absolute. But I did not feel any relief. Hearing the story, I felt a mixture of disdain for this dreadful CEO character and an overwhelming guilt that I couldn’t operate that way. The whole situation implied, given who was on stage and who was in the audience, that being hardcore and ruthless was the way someone becomes a winner in this place.

My character was the opposite of the archetypal Silicon Valley entrepreneur. I was risk averse, detail-oriented, introverted, allergic to exaggeration, introspective, highly sensitive to the emotions in the room, quick to take offense, and habitually scanning for danger. It quickly became clear to me that these traits were liabilities, beta characteristics that would get in the way of bold vision and ruthless pursuit, and they threatened to render me a failure while all the other valiant and strapping people in the audience around me rocketed forward in the race of life. Perversely, my unfitness for it all made me even more determined not to turn away from the icky scene, but rather to lean in, (and how that insidious phrase goaded me on). The goal posts had been set and I was in the game. I would show that I was a worthy competitor. I would show that I was the type of person that is talked about on stage.

Confession 3: How

I proceeded to play this game the only way I knew how, the way I had practiced for sixteen years in school: I tried to do everything exactly right. If only I did everything right, the logic went, I would succeed. I was in turn seized by a conviction that every minor decision I made would directly contribute to the success or failure of the venture, that anything that went wrong was absolutely the result of my own actions and that I must try harder, always. The sum of all my small decisions added together would reveal with final certainty whether or not I as a person was capable of being an entrepreneur, whether I could compete with the ranks of the newspaper-chucking CEO—whom I both hated and wanted to be?—indeed, whether I was capable of doing anything at all of value in this world.

Like every early startup, we were always one crisis away from collapse: our biggest customer teetering on the edge of leaving, our money endlessly dwindling, a critical team member giving notice, the product breaking in new and innovative ways. Each crisis, and my subsequent decisions, was a new trial for my personal worthiness. In year three, a competitor of ours reported our company to the federal government for an alleged infraction that could nullify our certification to operate. I spent three months making desperate pleas to government boards, engaging in rapid document creation, explaining and apologizing and acknowledging errors and creating written plans for rectification, and getting feedback on those plans and editing those plans and sending them again.

I vehemently disagreed with the complaint and simultaneously descended into a trough of self-hatred. I couldn’t bear doing things wrong, and now the US government thought I had done something wrong. I couldn’t bear people being angry with me, and now, the US government was angry at me. I stopped eating and sleeping as I waited for high-stakes calls to be scheduled with increasingly senior government officials. I furiously created PowerPoint slides, my comfort object. When I finally got on the phone, I groveled and begged and eventually hung up and cried and crawled into bed. Once, I vomited. These were not the hard edges of an entrepreneur. There were no sharp elbows, no bluster. There was fear and shame, and there were tears. I was the one having her proverbial newspaper ripped out of her proverbial hands.

I was miserable, that’s the confession. It hardly seems surprising or novel, but how many entrepreneurs just say it? My misery is stunning to me, given my privilege. I went to the best schools for sixteen years, I got a blue-chip job out of college. My parents provided me with every possible advantage. And yet here I was, lying face-down on my living room floor at noon on a Tuesday with tears soaking the carpet. Why the fuck was I doing this?

Confession 4: Why

How many times have I tried to explain why I started this company, to others and to myself? How many different versions have I told? I have said it was because I wanted to work with my brilliant cofounder, a man who is literally the most effective person I have ever met at doing almost any task. Of course I wanted to start a company with someone like that. I have said that I did it because I wanted to make an impact in the world, that I wanted to build something. I have said it was because being an entrepreneur would be a so-called “great learning experience,” (and doesn’t that phrase cover all manner of sins). Newly minted entrepreneurs love to point out how silly it is to pay for business school when you can get paid to “learn it on the ground.” I have said that, too.

These were all true enough, but there are certainly plenty of other ways to learn and build things and have impact and work with brilliant people that would not have caused me to literally barf. Besides, my goals were all very generic, very pre-baked for my generation—what self-respecting Ivy League-educated millennial in 2013 did not want to build something and have an impact while engaging in a great learning experience? Plus, look carefully at my internal logic: my day to day stress was driven by a sense that my personal worth would be determined by each decision I made, and whether those decisions amounted to the success or failure of the startup.

And how is the success of a venture-backed startup measured? Is it measured in whether you worked with smart people? No. Is it measured in how much the founder learned? Certainly not. Is it measured in impact? It is not, contrary to what founders like to say.

No, the reason I chose this path, the startup path, over all the others could only be one thing, really, and I’m not going to beat around the bush: I did it for the money. A successful startup is one that makes money, full stop. I was doing it for a shot at being rich. It’s the oldest story in the book, with only the gender updated: girl pursues wealth and becomes miserable. I knew this story. I was aware of the trap. I’m not surprised by it.

I’m only surprised to find that it happened to me.

Confession 5. The fancy school

I vividly remember the first time I encountered great wealth, in the form of a genuinely massive house. I was new in fifth grade at an all-girls private school, and I received a coveted invitation to Emma Hoffman’s house in Lexington along with a classmate named Xiaoxi. Emma led us through the house to her bedroom, a hike that seemed to take us some minutes, and I remember rounding a corner and looking down a hallway with light hardwood floors and what appeared to me to be one hundred closed doors stretching off into a distant horizon. Xiaoxi and I both gasped audibly. We stood gazing down the endless hallway, which could have been in a large office building but was actually in a house in Lexington belonging to a family of four.

What did I make of this scene at the impressionable young age of ten? I don’t remember feeling jealous. I was raised to believe that beyond providing a stable life for oneself and one’s family, the pursuit of more money was not an appropriate, worthy, or morally sound goal. My parents never said it so straightforwardly, but in the way parental beliefs are transferred through a thousand tiny observations, I knew this to be what we believed. We lived in a mixed-income neighborhood where my parents had progressed from owning nothing to owning a modest duplex with no garage and no dishwasher. From kindergarten through fourth grade, I attended a little school called The Neighborhood School, which was located in a small house in my neighborhood, selected by my mother for its values of diversity and community. My family took vacations to an inn in Vermont twice a year and we went to Cape Cod for one week each summer, all of which left an imprint of a genuinely idyllic childhood. We did not vacation in France and Hawaii. We did not spend eighty dollars on a pair of jeans.

My particular vacation and blue jean situation was oriented within a hierarchy for me when The Neighborhood School ended in fourth grade and I transitioned to the fancy all-girls private school. There, girls wore jeans that cost even more than eighty dollars and had second homes on islands off the coast of Georgia. My mom wanted me to attend a school called The Learning Project, but I wanted to go to Winsor. I knew, even then, that Winsor was the best, and I already knew I wanted the best. For the ensuing eight years I busted my little all-girls ass to continue my streak of being the best, among a group of girls who had already been selected as the best. The best, in this case, was defined as getting A’s on tests and getting into a top university. This definition of best came to me so early that it almost seems inborn. Later, my mom wanted me to take a year off before going to college, which I vehemently refused to do. I was an achieving little engine. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly where this came from, because it certainly wasn’t parental pressure. Genetics? Culture? The private education system? All of these and more?

At one point when I was in high school, still attending the private all-girls school, I recall telling my dad that I thought that making lots of money was a good goal, because it’s super tangible and then you can give it away to whomever you want. I remember him looking up from his Sunday Boston Globe, chuckling once, saying, “ok,” and then returning to the paper, and we moved on. Perhaps I was just trying it out. Perhaps I was expressing a genuine belief, which I would later push way down and wrap in other goals like impact and great learning experiences. Whatever prompted that outburst, I never said it again, and even then I knew to say aloud that the best thing about having money would be giving it away, and to keep silent the thought that the other best thing would be having a house with a hundred doors.

It is slightly comforting and fully horrifying that I was actually a perfect representative of my generation. One study looking at the changes in attitudes of college freshmen over 40 years showed that the number of students who place importance on making money nearly doubled between the 1960s and early 2000’s, when I was matriculating at a top university. Books have been written on the particulars of this shift, but suffice it to say that the cultural milieu in the United States increasingly encouraged a certain line of thinking, which I obediently adopted.

“I just want to look good,” I wrote in my journal during my junior year of high school, because my journal has always been the safest place for such confessions, “and to look good I need money.”

Confession 6. I broke

One of the early employees at my company was brilliant, as well as manipulative and belittling. She had an encyclopedic knowledge of our domain, and she wielded her knowledge to control my actions. She berated me if I wrote a blog post, saying I didn’t have the required expertise, or she told me that if I didn’t let her lead a certain phone call, she wouldn’t go to a conference I wanted her to attend. As a new manager and one of those twenty-something asshats with a business card that unjustifiably said “CEO,” I felt I had had no leg to stand on. I would bend and accommodate and apologize and, one time, tear up. Unlike our newspaper-throwing CEO, I had a deep insecurity about claiming that lofty title, and no desire to wield it. I was just little me. I was buying newspapers with my own pocket money and handing them out around the office—go ahead and read, folks! I just want you to like me! This particular employee needled my insecurity skillfully, assuaging what I came to understand as her own deep fears. Two sets of insecurities bumping up against each other daily, me cowering, her pursuing.

I knew I needed to fire her, but it was an unimaginable step to take. She was too brilliant, too knowledgeable, too fearsome. The growing certainty of the firing and the growing dread set up inside me and shredded my insides, causing waves of nausea. I needed to do it. I would do it if I were a strong and capable person. I couldn’t do it. Therefore, I wasn’t a strong and capable person.

One evening shortly before the firing, my boyfriend and I were preparing to go to a concert. I was whipping up a storm of self-hatred, furious at myself for being such an idiot and a coward, raging over my mishandling of everything and my stupidity for ever thinking I could be proficient at this endeavor, or really anything. Am I serious? I opened the refrigerator to look for a snack before we left, I was yelling now,

“What the fuck am I doing,” I screamed at myself, scanning the fridge.

“Rae…” my boyfriend said from the door to the kitchen,

“I’M SUCH AN IDIOT,” I screamed, and I dropped to my knees on the linoleum, the door of the refrigerator still open, casting a white light into the dusky kitchen. I squeezed my eyes shut against the glare and began sucking in air, suddenly dizzy. I put my palms on the gritty unwashed floor and crumbled into something like child’s pose, shaking uncontrollably, my body vibrating with nerves, air coming in as if through a narrow straw, the feeling of suffocation stoking my panic. My boyfriend came and hunched over me tentatively, completely unprepared for a panic attack, terrified, unsure what to do, saying,

“Rae? Rae...”

I crumpled into a fetal position and clutched my knees, muscles straining, hair splayed out among the crumbs, hands bloodless and numb, gasping, the bottom of the white kitchen cabinets coming in and out of focus.

In some ways, recounting the extraordinary stress I felt when running my startup helps me understand the newspaper-throwing founder just a little bit. It seems likely that both of us suffered from excessive stress; he seemed to take it out on others while I mostly took it out on myself. I am acutely aware that there are far worse, unelected ways to suffer—poverty, sexual abuse, the untimely death of a family member—and I am not claiming victimhood. The facts show that I myself made all the decisions that led to my own suffering. And so, my question, still, is how I could have possibly made those decisions, and how I could have possibly kept going when I was miserable and had so many other options, kept going even when the damage became so glaring and scary.

In my kitchen, I eventually stopped shaking. My breath stabilized and I emerged from the terrifying feeling of suffocation. The next day I went to work and took calls. I drafted documents, I responded to inquiries, I smiled in meetings.

Confession 7. But why

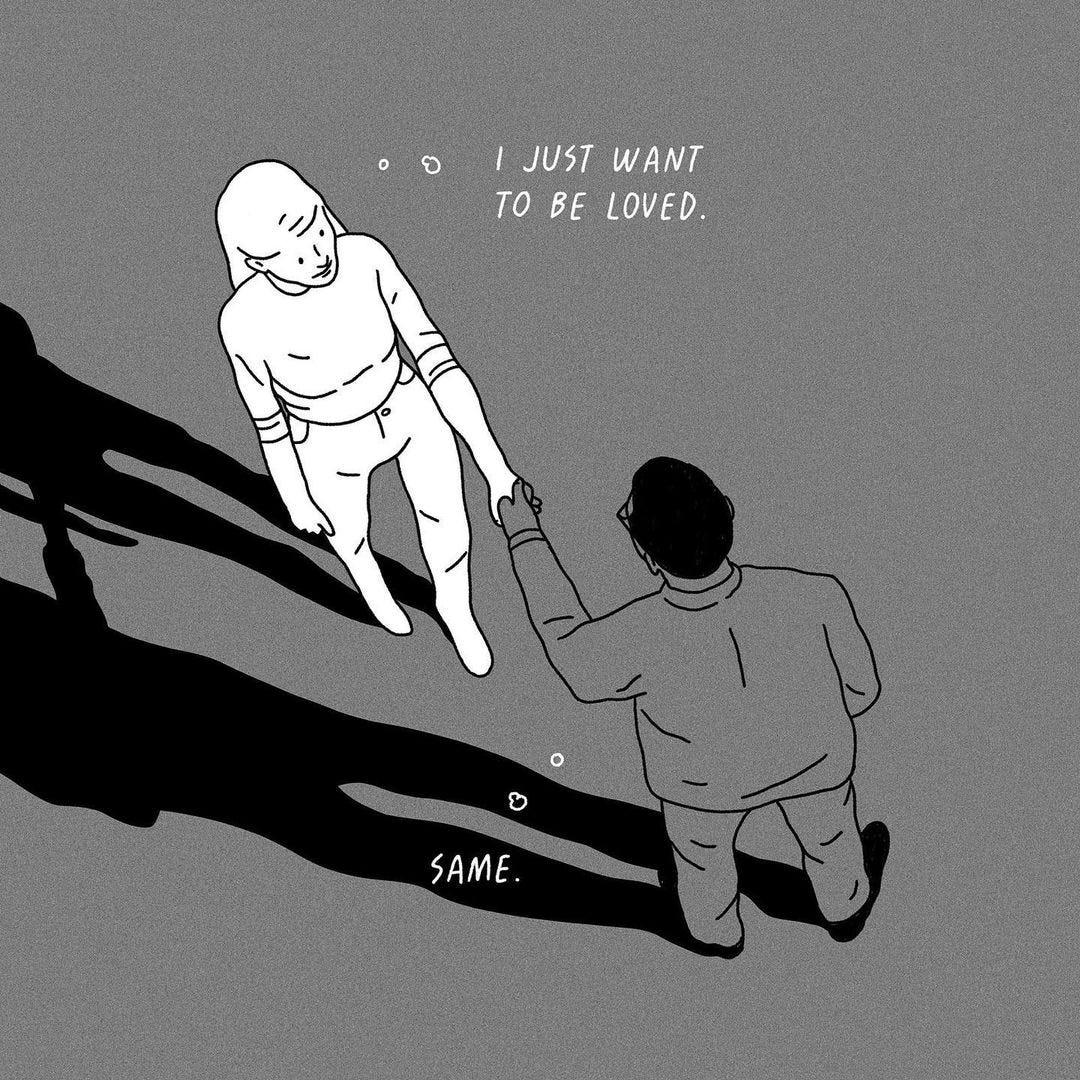

It seems baffling that I continued. But also, so many people like me do. People who don’t need more money regularly go to great lengths to acquire more money, often to the detriment of their health and happiness. Philosopher Alain de Botton explains this phenomenon with the concept of Societal Love: the love and adoration that a person receives from the people around her.

“We should not be surprised,” he writes, “to find many of the already affluent continuing to accumulate sums beyond anything that five generations might spend. Their endeavors are peculiar only if we insist on a strictly material rationale behind wealth creation. As much as money, they seek the respect that stands to be derived from the process of gathering it.”

Societal Love, Botton posits, is a twin pillar of romantic love, and we seek it with the same ardency. It is awarded in a variety of forms, like being featured in magazines and being asked to speak on panels and people generally caring who you are and what you think. This type of high status, Botton suggests, “is thought by many (but freely admitted by few) to be one of the finest earthly goods.”

In Silicon Valley, I existed in a world where Societal Love was doled out with special abundance to rich people. While there are certainly ways to earn it other than amassing wealth, particularly in smaller communities—being an artist, being a community leader, being an expert, being a good neighbor—being rich is by far the most common and certain way to be adored by my culture. With money, in other words, I had the potential to transform from the girl in the audience to the man on stage, or even the man being talked about adoringly by the man on stage.

Unfortunately for me, for us, even recognizing this reality, even acknowledging that I have fallen prey to the love-money trap, does very little for my deepest understanding about how to earn love in my world. The cultural conspiracy to equate the two is so complete, the magnetism of the love given to the rich is so strong. This tension lived in me, under the surface, as I grew my company: knowing on one level that it was a misplaced desire to yearn for excessive wealth, but still, somewhere else in my silly brain, ardently wanting the exact type of success that I hated, not quite understanding why, upset at myself for wanting it, not really having the time to consider any of this deeply. Now, looking back, the drama of my disintegration makes more sense. The lengths I was willing to go make more sense. I gave everything, and love is the only thing that could possibly balance that awful equation.

Confession 8. I did make the money

Here is the end of my startup fairy tale: I sold my company. This is the hardest confession of all for me, confessing that I ultimately benefitted so much from participating in a system that I think is damaging for people and for the world. My sale was not a big success in Silicon Valley terms—I got my investors a moderate 2-4x return, not the 100x they hope for. During the sale process, trying to dissuade me from selling so that I could go bigger, one of my investors told me that the amount of money I would get would not make any impact on my life. This prediction was flatly wrong. The grandest tangible thing I bought was a house for my family, nestled on a hillside in San Francisco. I also bought us longed-for financial stability after years of credit card debt. These are major advantages that most Americans are systematically kept from achieving, and buying myself financial security while living in one of the most expensive cities in the country was absolutely part of what I wanted when I decided to start a company.

What I didn't realize, though, was how much of the money would go toward undoing damage I had done while working like I did, hurting myself like I did, underpaying myself, straining my relationships, pushing my body and mind past their reasonable limits and into a state of constant crisis. I bought time to recover and process the experience, time to not feel constantly under stress, time and resources to deal with health issues like infertility and autoimmunity. I bought myself a chance to repair the damage that my stress wrought in my relationship with my husband, and to rekindle friendships that I had neglected. Given my privilege from the jump, I had so many other options to achieve financial security that wouldn’t have required putting all my chips on the table like I did, and that also would have never resulted in a windfall. In the aftermath of it all, the question of whether it was worth it looms large, floats in the air around me, unanswered.

So now here I am, possessing some material stuff that has undeniably improved my life, my moral compass screaming at me for all the wrongness involved in getting said stuff. The money is so helpful and welcome and also so tainted and heinous. I think this conflict will always be with me, and I try to welcome it. Having made the money, I should be turning over and over the question of my advantages, trying to figure out what my responsibility is now. Should I give it all away? Ugh, well, I know that I’m not going to do that. Then how much should I give away, and to whom? How do I, personally, define enough? How do you?

There was a viral article a few years ago by a female author, Jessica Knoll, who describes herself as someone who just wants to be rich. She argues that women should be able to be as baldly wealth-seeking as men, and should not be judged for it. She wants to be a billionaire, she writes plainly, she wants to be able to jet to Mexico on a whim. So sue her.

While I appreciate her boldness, I strongly disagree. I don’t think that greed and hoarding is an ideal end state for feminism, even if men have heretofore been celebrated for these behaviors. I finished the article curious whether Knoll has ever considered her personal definition of “enough,” or whether her view is that more is always better. In a small way, I envied her clarity. Can I just make a lot of money in peace? The answer is and should always be, no. It is inconvenient for the wealthy to contend with the impacts of wealth accumulation. It’s also essential.

*

It is easy for me, with the self-hating tendencies you have seen on display here, to blame myself for getting swept up in the game, for just not having the spine to resist the rush of ascending. But if I’m a little less harsh, I can also see that I was just a flawed human operating in an environment of treacherous rewards. How many other people are like me in that way? Perhaps it isn’t reasonable to ask each individual to internally hold such a steely pillar of values that no external perception can affect her. We are communal creatures, and setting that high a bar for individual ethics doesn’t seem realistic or even desirable.

I remember once, before I started my company, when I was working at a top consulting firm, a partner from the Hong Kong office said to me casually over a sushi dinner,

“In Hong Kong, you can have twenty million dollars and still feel poor.”

It’s an unbelievable statement, and also, I believe it. He was describing the force that our culture so effectively generates, the force to which so many of us are subject. This is the force that we must fight against, if we ever want to feel satisfied, and if we want even a shot at a more equitable world.

So, may I make this pitch, the culmination of my life’s story up until now: it matters whom we put on the stages of our world, whom we adore. Our collective love has been wildly misappropriated, particularly in Silicon Valley, but also all over the place. We give it, mostly, to rich people. Combine this with the fact that our economic structure leaves most Americans living in a state of constant, highly stressful, economic precarity, and it’s no wonder that so may people want to be rich.

I am not the best spokesperson for defying our cultural lust for wealth, having done what I’ve done. But I see it now, I see it like dust hit by sunlight, suddenly everywhere around me, in me. The best I can do now is avoid falling for it again.

Thank you.

Thank you for holding space for this exploration. I know these topics are fraught, complicated, and nuanced. They bring up so many feelings in me, and I’m sure they do in you, too. I’ll be writing more about money and power, greed and suffering, and I invite your feedback and experiences along the way. These are important conversations, and I want to have them with you.

Tell me:

💰 Have you investigated your own desire for wealth? If so, what did you find?

🤲 How do you determine what is “enough”? What does it look and feel like to you?

🏡 When did you first become aware of class?

Let’s discuss in the comments.

This is the most real founder tale I've ever seen. Keep it up.

Thank you for being so vulnerable and authentic. I'm working on a story now called "An Ode to Sleep" and reflecting on my time when I fancied myself an entrepreneur in my 20s, too important and too busy for such frivolous pastimes as sleeping. Then I had kids and realized that while sleep deprivation in the name of Achievement is a badge of honor, sleep deprivation in the name of Caregiving is just tiresome, and no one wants to hear about it. It's not until I experienced the latter that I realized how ridiculous our culture of overachievement is, how we neglect our own health and our community health in the name of glory and wealth, all the while trying to convince ourselves that whatever product, app, or service we're peddling is actually life-changing, paradigm-shifting, the pinnacle of innovation. I believe more women, especially, need to speak up rather than trying to fit ourselves into pre-conceived notions of how leaders or entrepreneurs "should" act. That's what I'm trying to do on Substack, and I'm grateful for your company!