If you were rich, would you fold laundry?

And: what would it look like to give all life tasks the time they take?

Most Sundays around 5 pm, I remember with dismay that I have not yet folded the laundry, and I feel like I do not have time to do so. Around that hour on a typical Sunday, my husband is prepping meals for the week against a backdrop of beat-forward electronic music, and my son is wearing socks on his hands and starting to get hungry. I exit the chaotic scene a bit guiltily to go sit on the bed, listen to an audio book, and fold. I make it halfway through, and then leave piles of onesies scattered across the duvet as I rush downstairs and relieve my cooking husband of a screaming toddler. Later, when the child is asleep and the kitchen counters are wiped and I’ve drank my magnesium powder and drowsiness has settled into my body, I turn the corner into my bedroom and realize with a jolt of annoyance and stress that I have not yet finished folding and cannot fall into bed because it is covered in laundry.

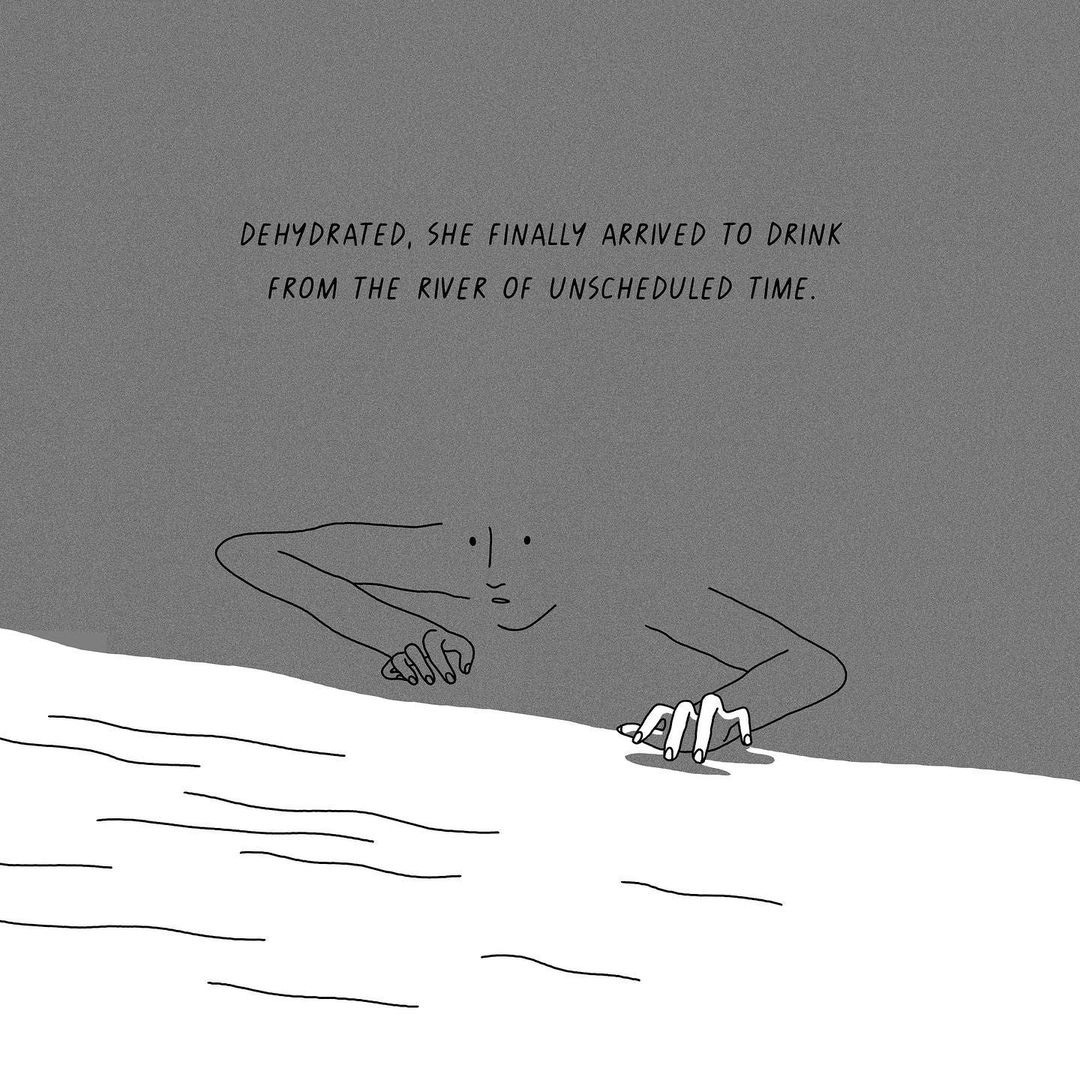

What interests me is that this pattern is the rule rather than the exception. My life is far less scheduled than it used to be, with far more space—a project I have been working on for years—and yet I have not achieved a state where I predict and allow for the amount of time that it takes to fold laundry. To say it differently, I seem to have organized my life under a false and continually disproven assumption that laundry folding can be done in less time than it actually takes.

I think this is a hallmark of the modern professional:1 we chronically underestimate the time needed to maintain a life, we believe ardently that such tasks should be squeezed invisibly between actual work. This little delusion is, I think, required by the demands of modern professional schedules. What would a week look like where all the tasks of living were given the time they require, with a little extra buffer? What if I calculated all commuting time as if I might hit the red lights, and I accurately assumed grocery shopping would take an additional twenty minutes due to a toddler in tow, and I expected that there would be medical and dental appointments, and I set aside time for handling household items that will inevitably break and need fixing, and I acknowledged that packing for a trip takes a certain amount of time, as does unpacking? How would my week look? Would the full set of activities require a dedicated hour each day? Two dedicated hours?

Two dedicated hours each day for completing the tasks of living. It sounds both completely reasonable and utterly impossible.

Advice from the Top

For the first three years of my ambitious business career I worked for McKinsey & Company, the elite consulting firm that has recently been repeatedly disgraced by scandal. Those scandals probably barely made a dent, though: the firm is a juggernaut. The McKinsey San Francisco office is located on the 45th floor of the old Bank of America building in the middle of downtown. The office has dark wooden built-in desks and glass walls that offer a 360 degree view of of the city, roads stretching out below towards the ocean on one side and the bay on the other, as if emanating from the firm itself. From that office I could watch the sun set over the ocean, nothing in the world to obscure my view, the full spectrum of visible light on display like I was the only person in the planet’s own movie theater. People at McKinsey spoke of intrinsics: the inborn qualities that set employees of the firm apart from the rest of the people, puttering around ant-sized forty-five stories below. In this context, at age twenty-two, it is easy to believe that anyone in that rarified place must be right, basically about everything. How else would they have gotten there? It is a dangerous situation for a young person.

I remember a McKinsey women’s event where fifteen or twenty young consultants from the San Francisco office sat around a glossy oval table listening to a junior partner speak about her successful ascent. The topic turned to work-life balance, as it always did at such events, and she advised us as follows: If there is a household task where it matters that you do it, then do it. If the task is agnostic to you, then outsource it. I vividly remember her examples:

Putting your children to bed? It matters that it’s you—you should do it.

Laundry? Doesn’t matter who does it—outsource it.

Made sense to me. I was twenty-two. She was successful. We were in an office with marble countertops in the kitchenettes. Who was I to argue?

***

I’m sure that for some readers, this whole story sounds grotesque. There are lots of reasons to feel that way, not the least of which is the wholesale diminishment of the people who would do the laundry within this framework. I imagine for other readers, there are elements of the advice that might seem reasonable. We’re busy, young kids, etc. For my part, I find the advice grotesque and I currently pay for two women to come vacuum and clean my kitchen and bathrooms two times a month. It is an extraordinary luxury. The fact that I do this complicates my position on the subject. But that’s what makes it interesting.

For me, looking back on that advice now with over a decade of distance, I am most interested in what that junior partner’s advice implies about living—that tasks like laundry folding don’t matter, and anyone who is able to should reinvest the time that we would spend folding laundry into higher-value activities, namely those that make money. I imagine this taken to the extreme: an allegedly frictionless life with no laundry folding and no cooking, no dishes and no cleaning sinks, no grocery shopping. Our cultural vision for the good life is shaped by powerful people at top, and this seems to be the vision. Erase that menial stuff, only do the good stuff.

Three legs of living

Here’s the problem I see with that: optimizing for the most possible paid working time would make me absolutely miserable. In the job at McKinsey, which I hated, more hours would only make me sicker and meaner. In a job I love, writing, I simply cannot be genuinely productive for more than a handful of hours each day.

You might respond that paying other people to do all of the maintenance tasks would allow free time for all the things the I want to do, my hobbies and passions, my creative pursuits. But my experience with extravagant amounts of undirected free time is that it’s pretty stressful. One can easily feel adrift and useless. Just a guess, but it seems to me that it’s a rare person who can enjoy many weeks of time with nothing particular they need to do, and not fall into some version of depression or numbing (television, drugs).

An ideal is emerging for me, a triad of types of work: The work you do to get paid, the life maintenance tasks like laundry, and the creative things you do for you. The economy-oriented work, the basic needs work, and the soul work, each of which brings something different to a full life. Three legs that create a solid foundation. I think the benefits of the paid work and the creative work are more obvious, but I would argue the maintenance work also has benefits. The role of these tasks in this triad is to anchor me to the world. They remind me how life is sustained. They remind me to value such work at the level it should be valued.

Imagine a life where each of these three legs get equal time. It goes without saying that this is not possible for almost anyone today, the demands of our economy don’t allow for it. But in the US, in this time of plenty, we are having the cultural discussion about what the hell to do about the fact that we can create so much wealth with so few people.

What if more people, all people, really did live life free from financial woes, a life with plenty of time and space? In that idealized world, perhaps the assumption is that everyone would emulate rich people today, offloading all the labor of life sustenance. Besides the fact that this is not a possible reality for everyone at once, (though I’m sure some are now thinking of robots), I do think something profound is lost when we lose a connection with the repetitive acts of washing and feeding. Most people reading this have already lost a connection with much of the work required to eat, and I think many, at least around me, feel something deeper has already been given up there, resulting in a whole lot of backyard garden beds.

So, I am experimentally proposing an ideal vision where everyone’s life looks more like the three-legged stool: held up by equal parts paid work, life maintenance, and creative pursuits. This would require the people at the top to do our typical paid work less, something we have so far been emphatically unwilling to do.

The facts remain: life maintenance tasks exist for every person, and they will always exist, whether “outsourced” or not, (how I dislike that word, its coldness and lack of humanity). The work we are prone to consider menial is foundational to a life, and I am suggesting a narrative where these tasks offer a break from other, more fast-paced modes of living, requiring a different type of energy and offering different rewards.

To me, giving laundry the time it actually takes, not trying to squeeze it in the corners, seems like a worthy goal.

—Rae

Thoughts on this essay?

As I wade into complex and hairy topics, I would love to hear your take.

I’m still working on my shorthand for “people like me”—highly ambitious? Trained to want it all? Concerned with the side effects of those qualities? Made sick by them?

I am a mother and a writer. I stopped practicing law when my second son was born. We have the money to pay someone to clean our house (weekly) and a sitter to mind my infant son so I can work for a few hours a day. (I agree that, as a writer, that's plenty.) Every morning I wake up and feel my heart swell with gratitude for these people, whose work I believe mothers me so I can better mother the kids. But: there will always be laundry. And dishes. And toothpaste foam pocked with cereal crumbs crusting on the bathroom sink. Who are these unicorns who can outsource every household task? In my experience, if there are children, the mess is a 24/7 event. I guess I don't feel bad about relieving myself of *some of it,* because there's always more to be done. And because I'm not overwhelmed by doing it all & alone, I can also find the meditative enjoyment in these acts of upkeep. I genuinely feel like our home is more integrated when I cook and just last night, doing dishes, I thought: "the soap is so warm on my hands, this is nice." Cleaning a kitchen at the end of the night is enormously satisfying. But that's because I wasn't also cleaning dishes from 7am that had piled up. I guess what I'm saying is part of my privilege is the privilege to enjoy what housework I have.

Beautiful. I get frustrated when people tell me to hire a cleaner, or buy meal prep kits to make my life easier....I like the headspace created while doing 'life maintenance' tasks. Life maintenance once consumed 95% our time and energy.....and it's wonderful that's no longer the case, but we don't need to endlessly attempt to shrink that number.