Against "having it all"

A career woman tries not to work

Recently, I’ve been thinking about tradeoffs. I am currently making some big ones, and I don’t feel totally settled about them.

I usually let some time pass before writing about the events in my life in this newsletter, but this dispatch is going to be a little more current, and a little more exploratory. Ever since I was a junior in high school, I have used writing to process my experiences, and this week I’m going to do just that. I’m curious to hear your thoughts and related experiences in the comments.

A little stage setting. I decided to devote this summer wholly to my family. Will and I moved ourselves and our kids into my parents’ house in Boston, leaving full-time childcare behind in San Francisco. We are in a unique and brief moment in our lives: we have two kids under three, we both have flexibility to be in a different location, my parents are vibrant and healthy grandparents, and we thought…let’s just go for it! It’s such a lucky set of circumstances, and all I want to do is immerse myself as fully as possible in this moment.

We are about a month in to our three-month stay, and I could write about the experience so far in two different ways. One: it’s a dreamy family summer filled with cuddles and birdwatching and pool splashing. Two: It is a complete surrender of my selfhood in service of my children.

Both are true, and I’d like to tell you about what I’m learning.

Story 1:

Could I ask for anything more than this? Each morning I am greeted by my chubby, cackling baby girl who snuggles in close for a long, satisfying drink. I didn’t breastfeed my older child for very long, so I didn’t get to know that physiological feeling of rightness that can happen when the baby latches and takes the first suck. The dose of oxytocin releases, and it’s like sitting down in a chair when you’ve been standing awhile—ah, everything is good. While she eats, I look out at the lush green foliage of the east coast summer and let myself relax into those good feelings.

My son wakes up chatty, and I listen closely. He tells me about the smoke alarm in the hallway, “that one is there for when we are sleeping, just in case, to call the fire department,” and then abruptly switches topics, “mommy this is my bracelet.”

The adults get up one by one, grab coffee, and spend the morning with the kids. My mom builds a block castle with my son on the floor, curiously trying to figure out what he means when he says, “this is a French block!” My dad patiently helps him fill the bird feeder, cup by tiny cup. We help him get ready for camp without the rushed feeling typical of mornings back home, and he marches out of the house in his bright yellow camp vest, a wide-brimmed hat, and pink heart-shaped sunglasses, which are his signature item lately.

In the afternoons we go to the pool to meet our cousins. Baby girl splashes herself in the face over and over, making a shocked expression each time, then immediately does it again. I hold her torso while she kicks her tiny feet powerfully, her diapered bum knocking against my stomach. These moments are as bright and hot as the Boston summer, as precious and fleeting. I can feel them being burned into my memory day after day, lines traced over until they are etched deep in the long-term part of my brain. My bond with each of my two children has continuously deepened and strengthened as we spend this intensive time together, I am familiar with their every little detail, at times I feel I can read their minds and they mine. I wouldn’t trade anything for this.

Story 2:

Or would I? Moving an almost-three-year-old out of his home and routine for the summer is a sure way to induce parental suffering. During the first two weeks in Boston, my son wouldn’t nap, resulting in bad moods and a resurgence of that particularly horrifying two-year-old habit of grabbing random things and chucking them across the room. Three hours of summer camp per day, it turns out, is not long, and the whole thing is particularly draining when he clings to my body at drop-off like I am about to throw him off a cliff, and I have to slowly peel him off and walk away while he screams. By the time I’m done with that whole thing I have about two hours before preparing for pick-up, during which time I had planned to exercise, write, work on my podcast, and generally do any other “me” things (lol I still haven’t learned). But as it turns out, it’s barely enough time to exercise and do one or two basic life tasks. And then the baby gets sick, and everything goes out the window.

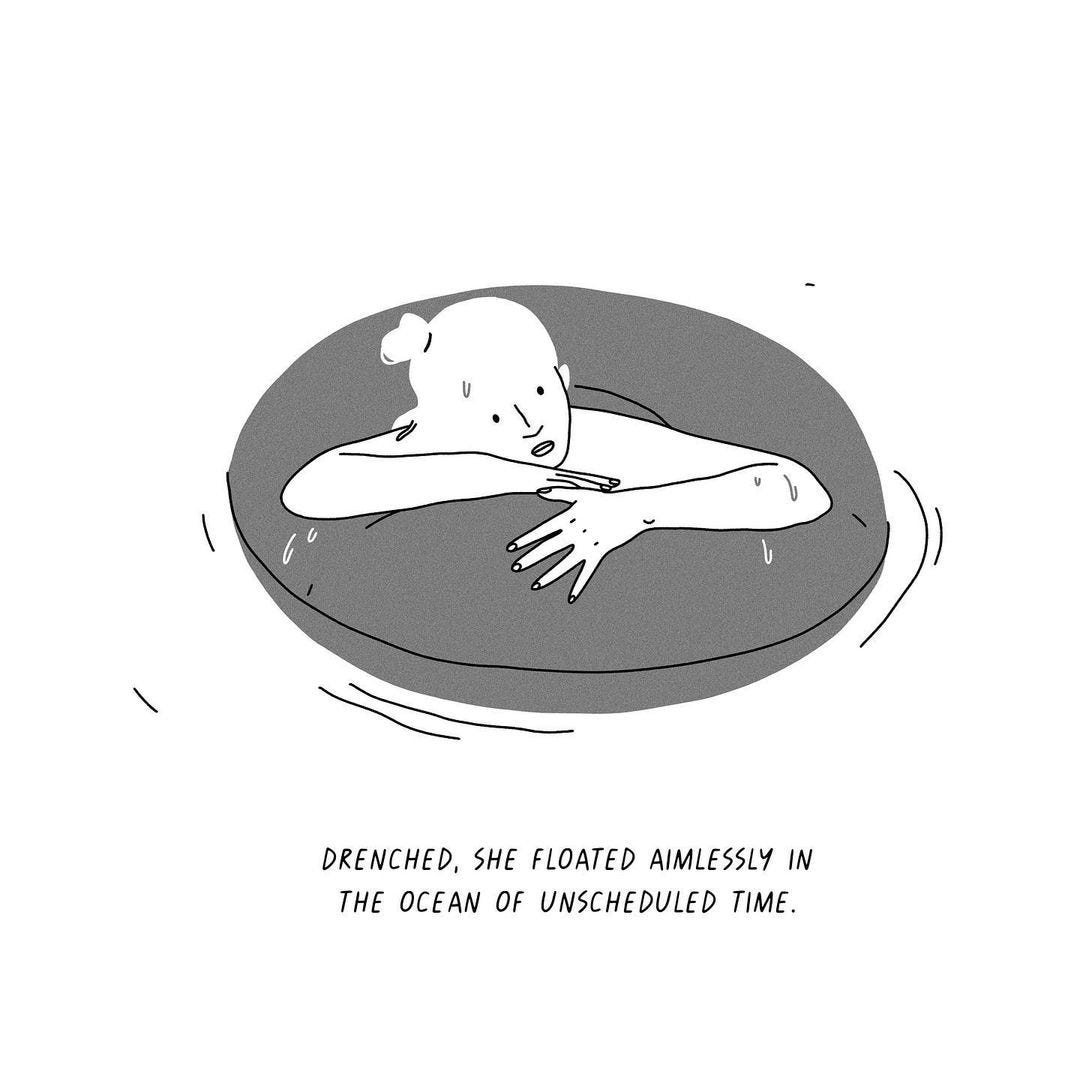

More broadly, the arrival of my second child ushered in a new era of subzero ambition, which is so not me. This highly disorienting change has left me feeling completely unmoored and, in many moments, anxious about what the future holds. There are number of projects I had been working on up the day before my daughter’s birth, all of which I was super excited about, which I now have absolutely no drive to continue. I have completely stopped working on the book I was writing. I am rarely interacting in Substack comments. A larger vision I had for community around chronic illness has fallen by the wayside. I can only manage one interview a month for The Lady’s Illness Library, my favorite project of all.

As someone who has had a strong work identity my whole life, I’m suddenly wondering who I am now. Beyond work, I have been more or less completely disengaged from the community land project that I adore so much. With few non-kid hours during the day, I have become worse at returning calls from close friends. Dang.

“It all” is impossible to “have”

One surprising thing about motherhood is how it keeps surprising me, even the obvious parts. I knew that there would be tradeoffs, anyone could tell you that, but there is nothing like having young children to remind you every moment that your allotment of time in life is finite, and making a decision to do one thing means not doing another. Day to day, the amount of time I choose to spend with my kids cannot be spent on other non-kid things, like work, personal projects, travel, exercise or connecting with my spouse one-on-one. If I choose to do these other things for an hour, I am not spending that hour with my kids. This is not up for debate, though even as I write it, I very much would like to believe there is some way around it. I began my career in the Lean In era and in the verifiable Lean In center of the universe (McKinsey & Company), and the message was always that, if you only were good enough, you really could have it all.

But what does “having it all” mean? What is “it all?” In so many ways, spending long summer days with my kids and my parents is as “having it all” as you can get. I do not, however, have the career I used to have, I do not have the external respect and self confidence that came with that. I do not have much of a sense of personal mission in the world outside of my family, and I do not have the satisfaction that comes with a job well done. I do not have the income I once had. I do not travel for work or to see the world. I do not spent long leisurely evenings with friends.

In his book Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, Oliver Burkeman states the obvious: “it all” is patently impossible to have. The book is about the finite time available in a life and ways to make the most of that time. One of Burkeman’s foundational points is that there are literally infinite awesome things to do in a life, and therefore, trying to do more won’t get you any closer to doing everything you could ever want, because you can’t get any closer to infinity. In fact, trying to squeeze more and more into a day will only make you feel like you are rushing through everything, and that tends to give the impression that life is passing you by.

When I read this, I immediately recognized it as true in my life. The more I try to squeeze in, the more I multitask, the more I am running from here to there, the less I feel like I had a good, long, satisfying day.

So in many ways, my young kids have helped me reorient the way I think about my time by making me more conscious of the tradeoffs I am choosing to make, something Burkeman says is critical to living a good life. Only with this consciousness can we actually choose to spend our limited time on the things that are most important to us. For someone who has long tried to optimize days to get more done and squeeze more in, the “do less better” approach takes some significant reprogramming, and this is work I want to do. Consider some of Burkeman’s suggestions for resisting time pressure and making life more spacious, all of which resonate with me:

Strategic underachievement: Deliberately doing less than you could in some areas to practice focusing on what's really important. This is what I’m trying to do with my work this summer.

Fixed time: Setting an amount of time for work each day or week and sticking to it regardless of how much work there is. Kid schedules force me to do this in a big way right now.

Buffer time: Building slack into your schedule to leave time for unexpected events and reduce the feeling of constantly rushing. This one is particularly hard for me in my regular life, but it’s especially effective when I actually do it. Additionally, rushing with a toddler is always a miserable experience, and the less I can do it in my life the better.

Avoiding multitasking: I’m generally fairly good at this, as long as my phone is not sitting next to me. If it’s next to me, I ALWAYS pick it up.

Limiting social media and email checking: This reduces demands on your attention, which allows you to focus on that important part of life happening in front of you. Again, phone placement is key for me. I don’t have social media but I fill that void by compulsively checking my email, even though there is absolutely no reason for me to do this.

Practicing presence: Using meditation techniques to stay in the current moment. I feel like “presence” is one of those words that is used so much that my eyes tend to glaze over it. But babies and toddlers offer a wonderful new avenue into presence by constantly modeling what it means to live in the moment, thereby inviting me to do the same.

Embracing missing out: This is the big one for me this summer. Accepting that I can't experience everything reduces feelings of FOMO. I am spending the summer deeply engaging with my kids and family. I’m not advancing my career or making a big impact in the world or traveling or going to parties or spending much time with friends. People doing those things are not doing what I’m doing. I am trying to view this situation as totally fine.

So here’s where I’m landing: one significant purpose of my summer is to practice these skills. This is three months we are talking about—not very long—it’s incredible how much confusion and lostness one non-work-oriented summer can generate in the heart of someone who has always built her identity around career.

Frankly, I don’t think my balance is quite right at the moment. I enjoy my time with my kids more when there’s slightly less of it; my feelings of self worth expand when I am engaging more in work projects, when I am on a team, when I am generating income for my family. After witnessing the damaging health effects of my former work life, leaving it all behind, and having two kids, I have pushed myself all the way to the other side of the pendulum, and it is leaving me feeling a little empty. I think there is a different balance that I would like to attempt during this period of life, one that is still highly kid-focused but has a little more space for non-kid endeavors.

But even if I land on a different mix of activities, it will not be “having it all.” It will be some set of tradeoffs that I make in order to do the things that matter most to me, at the expense of the many other awesome things that can be done in a life. I will lose some portion of the daily closeness I have to my children right now. So while I’m here in this family-oriented summer that I designed, I want to focus on practicing some skills of good living that I haven’t historically done well: planning in buffer time, embracing missing out, and staying present, to name a few. When I manage to hit these notes, the long, luxurious summer days become just that: the fullest and sweetest version of a day in a life.

What’s your current life balance? Do you like where it’s at?

And do any of Burkeman’s recommendations resonate with you?

I’d love to hear from you in the comments!

You certainly can't have it all all at once. But you can, over the span of your life, have an impactful career, spend loads of time with your family, and develop meaningful friendships. The counter to thinking of your time as finite is thinking of your life as long. Your days are short, and you can really only accomplish so much in a day. But if you consider you're allotted about sixty years of adult life, there's a lot you could have in that time. And: your identity doesn't have to be static. The most interesting characters are dynamic--they change. Give yourself the space to change, and change again--don't worry that "mother" has taken too strong a hold right now, because no matter what you will not always have two children under the age of three. Enjoy each day as the beautiful blip it is in the layering and multitude of all your days. 😊

My wedding planner told me, “You can have anything you want. You can’t have everything you want” and this is advice I have carried with me ever since. I only have one kid, and he is now 6, and this has been the most wonderful season of balance for me so far. He goes to full day camp or school, disappears into his room with friends or legos for hours at a time, just needs less hands on care and supervision than he did, and this independence gives my schedule the breathing room it needs for me to find my ambition again. When he was younger, the ages your kids are, I felt more like you do now and worried it would last forever. I’m currently working independently as a coach/consultant 10-25 hours a week, and spending the rest of my time investing in my relationships, painting, and generally living at the slower pace that works best for me and my family. There is a whole raft of luck and privilege that makes this possible, but also some significant lifestyle trade offs we’ve made. Because what I’ve learned is that having a slow and rich texture to my days, for me, makes me happier than any other form of achievement or success ever did. Maybe that will change? But the longer I live this way, the more I suspect it won’t.